‘Free’ sugar…but can we afford it?

Evidence shows that many of us are consuming too much of a certain type of sugar known as ‘free sugar’. This article asks what the implications of this might be for our health, how much free sugar we should actually be consuming, and what government organisations in Northern Ireland are doing to address the issue.

Sugar is deeply embedded within our food supply. Furthermore, sugar is often viewed as a source of calories that people don’t need. Yet not all sugar is bad. In appropriate amounts, sugar is used by the body as a source of energy to help maintain a healthy metabolism as part of a balanced diet.

What are free sugars?

Although many types of sugar exist, their definitions vary and this can be confusing for scientists and consumers alike. At a high level, sugars can be divided into two main types:

- naturally occurring sugars (such as those found in whole fruit and vegetables), and

- free sugars.

The World Health Organisation defines free sugars as:

‘all monosaccharides and disaccharides added to foods and beverages by the manufacturer, cook or consumer, plus sugars naturally present in honey, syrups and fruit juices and fruit juice concentrates’.

Foods containing free sugars are widely available and often subject to tempting marketing strategies and price promotions. Examples of foods high in free sugars include cereals, biscuits, pastries, sweets, and soft drinks. They can also be ‘hidden’ in products we might not expect – like sauces, soups and low-fat diet foods like yogurts.

So how harmful are they?

It is widely accepted that a healthy diet is a key factor in increasing life expectancy through preventing diet-related illnesses. But determining how harmful free sugars are can be challenging because of the difficulties separating specific ingredients in food products from dietary and lifestyle factors. Furthermore, working out how much free sugar an individual consumes per day is not easy. Currently food labelling legislation requires ‘total sugars’ to be displayed on product packaging, not solely free sugars.

Whilst there is no evidence of adverse effects of consumption of naturally occurring sugars, the case against the potentially harmful impact of free sugar – especially on children – has strengthened. Too much free sugar intake can increase the risk of:

- excess calories in the diet, leading to obesity. In Northern Ireland, 60% of adults and 25% of children are now overweight and obese;

- tooth decay (dental caries). According to the British Dental Association, Northern Ireland has the worst oral health in the UK, with 72% of 15-year-olds having tooth decay, compared with 44% cent in England;

- diseases like type 2 diabetes, stoke, heart disease and some cancers – although the evidence for this is less robust.

These conditions can lead to a range of health, social and economic problems, along with major costs to the NHS.

How much free sugar should we consume?

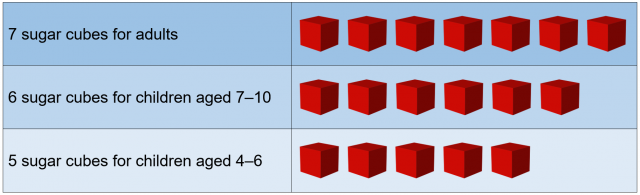

There have been increasing calls to reduce the level of free sugar consumed in our diets. In 2015 the World Health Organisation published guidelines which recommended that intake of free sugars should not exceed 10% of our daily energy intake, and that a further reduction to 5% would provide additional benefits. Similarly, the UK Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition (SACN) published recommendations that have been adopted by the Department of Health in England. The recommendations limit the intake of free sugars to no more than 5% of our daily energy intake. This equates to:

SACN also recommends that consumption of sugar sweetened drinks should be minimised by adults and children; on average, one fizzy drink can take a person over their daily recommended sugar intake.

Despite the SACN recommendations, a National Diet and Nutrition Survey conducted by the Food Standards Agency in Northern Ireland showed that:

|

So what action is being taken by the government in Northern Ireland?

In terms of policy, the Department of Health in Northern Ireland has advised that it does not have a specific policy or targets relating to sugar consumption or reduction. Yet it also states that it is guided by the free sugar SACN recommendations endorsed by the Department of Health in England.

The main policy from the Department of Health (Northern Ireland) of relevance to this article is A Fitter Future for All – the overweight and obesity framework. It contains general information about eating healthier, and preventative goals. These include the need to reduce children’s exposure to the advertising of sugary products (amongst other ingredients like fat and salt), to get the food industry to reformulate food, and for people to reduce portion sizes. There is also an outcomes framework with some actions relating to sugar – like identifying key foods with the highest sugar content and developing a programme of action to address it.

Similar to the Department of Health, the Public Health Agency (PHA) in Northern Ireland has focused on promoting a healthy balanced diet, rather than targeting any one specific food source. The PHA has published an Enjoy Healthy Eating booklet and healthy eating advice on its Choose to Live Better website, both of which highlight the need to reduce sugar consumption. Despite also endorsing the SACN recommendations, at the time of writing, neither the booklet nor website mention those recommendations, nor what specific levels of free sugar intake people should aim for. The agency has advised that it also provides more general healthy cooking/food programmes and is collaborating with other agencies to revise the mandatory Nutritional Standards for school meals to reduce sugar intake amongst pupils.

The Food Standards Agency (FSA) Northern Ireland has been leading on the reformulation of food. It has been scoping a programme of work to support local small and medium sized businesses to align with Public Health England’s ambition to remove 20% of sugar from nine high sugar food categories by 2020. The FSA appears to be the only government organisation in Northern Ireland currently to include the SACN recommendations about how much free sugar we should consume. This is contained in the Eatwell Guide – getting started.

In terms of legislation, the Health (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act 2016 contains a duty on the Department of Health in Northern Ireland to carry out a study on a levy on sugar-sweetened drinks within two years of its enactment. However, a levy on soft drinks proposed by the UK Government in 2016 will be introduced across the UK in 2018. This will include a UK-wide consultation which will negate the requirement for a separate Northern Ireland study. The levy, which has been contested by the soft drinks industry, will be imposed on manufacturers and importers (rather than consumer) in order to incentivise them to reduce sugar content and reformulate their drinks. It is estimated that around £380 million will be raised in revenue per year and Northern Ireland is due to receive its share of the revenue via the Barnett Formula. The money generated is intended to be reinvested in schools, through initiatives like sporting activities and healthy breakfast clubs.

Is the message getting through?

Compared to the level of action being taken on reducing free sugars in England, it remains unclear how the SACN recommendations are, or will, be embedded in policy or health campaigns in Northern Ireland. Whilst measures have been taken locally to tackle the amount of sugars generally consumed in our diets, it is unknown whether people are actually getting the message about free sugar. Yet, given the growing evidence about its potentially negative and costly health impacts, can we really afford not to?