This blog article provides an overview of educational underachievement in Northern Ireland. It defines underachievement, examines the attainment gap between pupils entitled to free school meals and others, outlines the causes of underachievement, public policy responses, and concludes with some observations on this complex issue.

Underachievement

Educational underachievement has been defined as:

…school performance, usually measured by grades, that is substantially below what would be predicted on the basis of the student’s mental ability, typically measured by intelligence or standardised academic tests.

Educational underachievement remains a persistent and seemingly intractable problem not just in Northern Ireland but across the United Kingdom and the Republic of Ireland. The typical metric used to capture underachievement is how well pupils perform at secondary school level (16 and 18 years) in GCSEs and A Levels respectively, not least because there are standardised ways of measuring educational outcomes at these points: at least five GCSEs (A*–C) including English and Maths; and 3+ A Levels grades A*–C, respectively.

The attainment gap

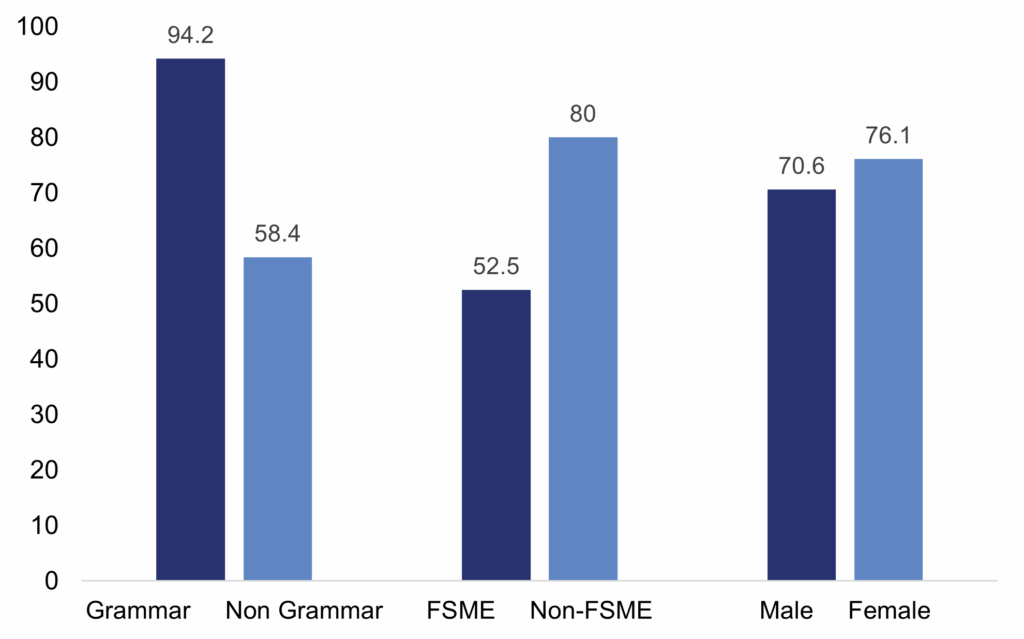

There is an educational achievement gap across school types, gender, and free school meals entitlement (a surrogate indicator of poverty) – see figure 1. In this blog article we focus on underachievement of those entitled to free school meals (FSME).

Table 1 lists the attainment gap across two points in time (2018/19 – 2023/24) for GCSE and A Level pupils. The data show that the attainment gap between those entitled to free school meals and those who are not eligible has increased at GSCE and A Level.

| Table 1: Year 12 examination performance 5+ GSCE including English and Maths | ||

| 2018/19 | 2023/24 | |

| Non-FSME | 80.2% | 80.0% |

| FSME | 54.1% | 52.5% |

| Attainment gap | 26.1% | 27.5% |

| Year 14 examination performance: 3+ A Levels at grades A* – C | ||

| Non-FSME | 74.1% | 73.8% |

| FSME | 61.1% | 58.2% |

| Attainment gap | 13% | 15.6% |

Source: Department of Education NI: Examination Performance Data 2023/24 DENI data

The causes of underachievement

To tackle educational attainment demands an understanding of its causes. The Expert Panel on Educational Underachievement noted:

Educational underachievement linked to economic disadvantage is an issue that has persisted for many years despite numerous policy interventions and significant financial investment by the Department of Education and others. Whilst some progress has been made, it is generally recognised that underachievement is due to its inextricable link with poverty in society, which is a much wider issue than education alone.

Academic studies provide a good understanding of the causes of underachievement. A Queen’s University Belfast study examined seven of the most deprived areas in Northern Ireland[1] and identified the following factors which inhibited educational achievement:

At Immediate (individual-home-community) level:

- Young people’s mental health issues

- Adverse home conditions and inadequate levels of parental support

- Inter-generational transmission of educational failure

- Low self-esteem and aspirations of some young people

At school level:

- Low expectations on the part of some schools/ teachers

- Weak school-community linkages

- Perceptions of some schools as ‘middle-class’ and ’detached’

- High rates of absenteeism and exclusion in some schools

- Insufficient support for SEN and behavioural problems

At structural/policy level:

- Current economic climate

- Legacies of the recent conflict

- Spatial detachment of schools and the communities they serve

- Variability in availability of quality pre-school provision

- Academic selection – negative effects

Research indicates absenteeism to be a significant cause of low educational attainment. Evidence shows that the students with the highest attendance throughout their time in school gain the best GCSE and A Level results. Absence is reported by schools in half-day sessions and recorded as authorised or unauthorised. Attendance data (2021/22) data show that for all schools, FSME pupils were absent for 13.1% of total half days compared with 8.4% for NFSME pupils, a gap of 4.7 percentage points (table 2). The difference in absence rates was greatest in post primary schools where the absenteeism was 15.6% for FSME pupils and 9.6% for NFSME pupils, a difference of 6.0 percentage points.

| Table 2: Absenteeism 2021/22 | |||||

| FSME | Percentage of total half days | ||||

| Attended | Overall absence | Authorised absence | Unauthorised absence | ||

| Primary | FSME | 88.7 | 11.3 | 7.2 | 4.1 |

| Non FSME | 92.6 | 7.4 | 5.4 | 2.0 | |

| Total | 91.6 | 8.4 | 5.9 | 2.5 | |

| Post-primary | FSME | 84.3 | 15.6 | 8.9 | 6.7 |

| Non FSME | 90.4 | 9.6 | 6.4 | 3.2 | |

| Total | 89.0 | 11.0 | 7.0 | 4.0 | |

| Special | FSME | 84.5 | 15.5 | 10.6 | 5.0 |

| Non FSME | 84.4 | 15.6 | 9.9 | 5.7 | |

| Total | 84.4 | 15.6 | 10.2 | 5.3 | |

| All schools | FSME | 86.9 | 13.1 | 8.0 | 5.1 |

| Non FSME | 91.6 | 8.4 | 5.9 | 2.5 | |

| Total | 90.4 | 9.6 | 6.4 | 3.2 | |

Source: DENI and NISRA Attendance Data 2021/22

Academic studies also provide a more detailed analysis of the link between attainment and socio-economic factors. In research using data from 22,764 school leavers in Northern Ireland which examined their educational outcomes, the findings were as follows:

- Girl school leavers significantly out-perform boys regardless of how deprived the areas in which they live.

- Catholic school leavers significantly out-perform Protestant school leavers regardless of how deprived the areas in which they live.

- Areas suffering from high levels of multiple deprivation have the lowest levels of educational performance, particularly marked amongst FSME male school leavers.

- The likelihood of good examination performance is highest amongst NFSME school leavers.

- The school leaver most likely to obtain good GCSEs is a NFSME, non-SEN, Catholic female from an area with low levels of deprivation.

- The school leaver least likely to obtain good GCSEs is a FSME, SEN Protestant male from an area with high levels of deprivation.

Policy responses to tackle underachievement

The above research indicates broad agreement on the causes of educational underachievement. The critical question is what have been the policy responses aimed at tackling the problem? The Independent Review of Education listed several policies funded by DENI aimed at addressing educational disadvantage: including Targeting Social Need (2005), Extended Schools (2006) and Full-Service Programmes (2006 and 2009), the Pathway Fund (2016), Getting Ready to Learn – Early Years (2017).

In July 2020 the (then) Minister of Education (Peter Weir) set up an Expert Panel to examine educational disadvantage as a commitment made from the New Decade, New Approach agreement (2020). Its terms of reference included: to examine the links between persistent educational underachievement and socio-economic background (with a particular consideration given to working-class Protestant boys) and a costed action plan to address the problem.

The Expert Panel produced a final report and action plan in May 2021 entitled A Fair Start. The report suggested a focus on eight broad areas as follows:

- Redirecting the focus to early years.

- Championing emotional health and wellbeing.

- Ensuring the relevance and appropriateness of curriculum and assessment.

- Promoting a whole community approach to education.

- Maximising boys’ potential.

- Driving forward teachers’ professional learning.

- Supporting the professional learning and wellbeing of school leadership.

- Ensuring interdepartmental collaboration and delivery.

The Independent Review of Education (2023) was initiated as a key commitment within the New Decade, New Approach Agreement in recognition of the need to reform and improve the education system, particularly around issues of underfunding, special education needs, curriculum and assessment, governance and collaboration.

The Independent Review noted:

There is no “silver bullet” when it comes to reducing the educational effect of disadvantage. Ultimately, it is essential that all learners be provided with the conditions where they can remain engaged and thrive in education.

The Department of Education endorsed the recommendations of the Fair Start report. As a result, the Minister (Paul Givan) announced the RAISE programme (31 May 2024) with a budget of £20 million over the next two years described as a ‘whole community and place-based approach’. Criteria for funding within this programme have moved beyond traditional FSME eligibility to include data on: GCSEs, absenteeism, SEN pupils, FSME, multiple deprivation indices (income deprivation affecting children and health deprivation and disability), and crime-anti-social behaviour incidents.

Evaluation

Evaluation of the success of these policy interventions has been mixed, not least because the attainment gap remains stubbornly significant between FSME and NFSME pupils over time.

The Northern Ireland Audit Office (NIAO) published a report (2021) entitled Closing the Gap – Social Deprivation and Links to Educational Attainment. The Audit Office focused on two DENI-funded interventions aimed at tackling the attainment gap: Targeting Social Need and Sure Start. The Audit Office findings were damning:

Over £900 million of funding (for these two interventions) has not made any demonstrable difference in narrowing the educational attainment gap between disadvantaged pupils and their more affluent counterparts… it is simply unacceptable that the Department (DENI) does not have adequate information to establish how these funds have been targeted by schools, or the effectiveness of the interventions used.

The Audit Office did, however, acknowledge that a broad range of factors could impact on educational attainment including school leadership, classroom teaching, and parental and community involvement.

We summarise the causes of educational underachievement, micro-meso policies aimed at addressing the problem, macro initiatives, and issues which remain to be addressed in Figure 2.

Some final observations

- Educational underachievement remains a persistent and seemingly intractable problem not just in Northern Ireland but across the United Kingdom and the Republic of Ireland.

- The causes of, and factors contributing to, underachievement are now well-known. The policy responses to tackle the problem could be described as eclectic, experimental and not always well-evaluated.

- In some cases, there is conflicting evidence as to the merits of policy interventions such as Targeting Social Need. The NIAO report was highly critical of this initiative, yet schools self-report its effectiveness. Similarly, Northern Ireland Sure Start was criticised by the Audit Office but praised by recipients in the Fair Start report.

- The Education Minister (Paul Givan) has highlighted tackling educational disadvantage as one of his priorities in response to the Independent Review of Education (2023).

- The metric for tracking underachievement is gaining less than five or more GCSEs at A*-C (including English and Maths). Although this allows for year-on-year comparisons, it captures the problem too late in the cycle of pupils’ learning journey.

- Research shows that the attainment gap opens up from pre-school. We know, for example, that poor school attendance is a key cause of low educational outcomes. Monitoring attendance at Key Stage 4 is simply confirming the obvious link to poor examination results.

- There are examples where schools with a high number of free school meal entitled (FSME) pupils perform well, the Council for Catholic Maintained Schools (CCMS) non-grammar sector in particular. These schools offer opportunities for shared learning from their experiences.

- Education as a policy area, and tackling the attainment gap, has a low profile in the Programme for Government 2024-27. There is one reference to the school leavers’ attainment gap in the accompanying Wellbeing Framework. In the face of other competing public policy priorities, it will be important to track progress to ensure policy implementation on tackling underachievement.

- Much of the existing academic research and policy papers emphasise the role of cross-departmental collaboration in tackling the multi-faceted problems associated with educational underachievement. Joined-up government on this issue has proved particularly difficult to achieve in practice.

_____________________________

[1] These are: Whiterock, The Diamond, Woodstock, Duncairn, Rosemount, Dunclug and Tullycarnet.