The draft Programme for Government contains a commitment to running a pilot family drug and alcohol court in Northern Ireland. Such courts have been used in England for some time, but what are they and how effective have they been?

Family Drug and Alcohol Courts (FDACs) currently exist in some parts of England, but up until now Northern Ireland has taken a different approach to these difficult cases. They are designed as an alternative way of supporting parents to overcome the substance misuse, mental health and domestic abuse problems that have put their children at risk of serious harm. FDACs are intended to offer parents optimism about recovery and change, combined with a realistic understanding of the immense challenge they face. There are currently thirteen FDAC teams across 21 local authorities in England, sitting in a total of sixteen courts.

How do FDACs work?

The FDAC problem-solving approach in court is about hearing cases in a collaborative rather than an adversarial manner.

Cases are referred into FDAC by local authorities. This can happen as part of pre-proceedings activity or when the local authority is issuing care proceedings. There is discussion between the local authority and the specialist team before any referral. The process followed by the team is similar whether the case is in proceedings or not.

Substance misuse specialists and social workers from the team carry out an early and quick assessment of the parents. An intervention plan is agreed at a meeting attended by the parents, social workers and guardian. The parents then begin a ‘trial for change’. The team provide a key worker who does direct work with the parent and co-ordinates all the services identified in the plan. The team also carry out drug and alcohol testing, and in cases in proceedings they prepare regular short reports on the parents’ progress and they attend court reviews. Intervention planning review meetings are held at regular intervals, to agree any changes to the plan and decide on future action.

There is regular communication between the team and the judge in relation to cases in court, and between the team and relevant adult and children’s services. Housing services and domestic abuse services are also involved, along with legal representatives.

A key aspect of the model is that it works independently of the local authority. This means independence from the children’s social care team and the local child protection and children in need teams.

FDAC’s main features are judicial continuity, involving fortnightly judge-led review hearings without lawyers present where judges use motivational interviewing techniques with parents, encouraging parents to seize every opportunity to turn their lives around for the benefit of their children.

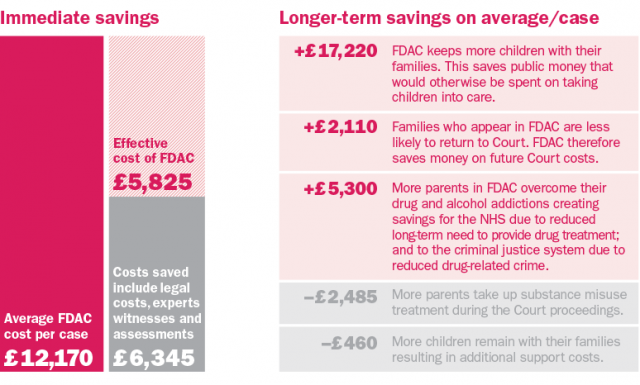

What do FDACs cost?

A 2014 assessment of FDAC explained the complex ways in which such cases are funded:

Since April 2012, the FDAC specialist team has been funded by five inner-London local authorities, with commissioning arrangements agreed year by year. One local authority retains the lead for commissioning and, as part of this, negotiates the service level agreement with the two providers, the Tavistock and Portman NHS Foundation Trust and Coram. The funding is based on an average cost per case, with each local authority buying an agreed number of case slots, up to an overall maximum of 47 for the year. The funding comes from Children’s Services departments only. There is no funding from health, adult services or the Legal Aid Agency.

The FDAC National Unit received funding of £3.2m from the Department for Education’s Innovation Programme. The government grant covers the work of the National Unit and also provides each new site with half the cost of setting up their specialist FDAC team, with matched funding provided by the local authorities.

While funding is a concern given the budgetary constraints that many local authorities are faced with, the organisation states that the savings they provide are beneficial to the ‘public purse’.

Does FDAC get results?

A study published in September 2016 followed up those cases which were first assessed in 2014. The study found that:

- A significantly higher proportion of FDAC than comparison mothers had ceased to misuse by the end of proceedings (46% v 30%);

- A significantly higher proportion of FDAC than comparison families were reunited or continued to live together at the end of proceedings (37% v 25%);

- A significantly higher proportion of FDAC than comparison reunification mothers (58% v 24%) were estimated to sustain cessation over the five-year follow up;

- A significantly higher proportion of FDAC than comparison mothers who had been reunited with their children at the end of proceedings were estimated to experience no disruption to family stability at 3 year follow up (51% v 22%).

What is the situation in Northern Ireland?

So far, Northern Ireland has not had Family Drug and Alcohol Courts. However, a recent OECD Review examined the scope for expanding problem-solving justice in Northern Ireland. The review made a number of recommendations. It found that there are already a number of operational practices found here which could be thought of as aligning with problem-solving principles in that they are aimed at understanding the offenders’ context and situation. For example, such practices include:

- Pre-Sentence Reports (PSRs): The Probation Board Northern Ireland (PBNI) prepares a pre-sentence report in order to assist the court in forming sentences which take account of the circumstances of the offender. A number of interviews with the offender may be conducted and the impact of the crime on the victim and the personal circumstances of the offender are important topics of conversation during the interview.

- The Assessment, Case Management and Evaluation System (ACE): This is designed to help the probation officer to assess the likelihood that reoffending will occur within a two-year period. Data from 2013-14 indicate that of those offenders who underwent an ACE assessment, PBNI assessed the probability of re-offending as low in 20%, as medium in 51%, and as high in 29% of cases.

- Enhanced Combination Orders (ECO): These orders represent a community-based alternative for the increasing number of custodial sentences of up to 12 months. They ‘focus on rehabilitation, reparation, restorative practice and distance’.

The OECD review recognised that there are significant pressures on public spending in Northern Ireland and recommended that an ‘incremental approach’ could be pursued.

…Northern Ireland may consider embracing a gradual approach to adopting principles of problem-solving justice and strengthen problem-solving elements in different parts of the existing justice chain.

A Review of Family and Civil Justice is currently being conducted by Lord Justice Gillen and a draft report recommends that the introduction of Drug and Alcohol Courts be considered. In a recent interview published in The Detail, Lord Justice Gillen highlighted the potential benefits of reform across the family court system in Northern Ireland and noted the long term savings and family benefits that problem-solving courts could potentially provide.

During the Consideration Stage of the Justice No 2 Bill, debated in plenary on 10 February 2016, the previous Minister of Justice indicated his interest in new opportunities presented by broader problem-solving and community approaches. He indicated that he:

…would like to see more work done in future to explore the benefits of such an approach for our justice system… many of the problems in society that bring people into the justice system will require commitment from Health, Education and, sometimes, other partners as well. The development of a Programme for Government for the next mandate is the opportunity to think strategically about the outcomes that we want for society, and I believe that problem-solving approaches will have a role to play in that.

Indeed, during the previous Assembly mandate the Chair of the Justice Committee expressed his support for the idea of problem-solving courts. The Committee published a report on Justice in the 21st Century: Innovative Approaches for the Criminal Justice System in Northern Ireland. It made a number of recommendations about problem-solving courts, including the following:

The Committee is of the view that the underlying problems and root causes of offending behaviour in a range of areas such as alcohol and drug addiction must be tackled if reoffending rates are to be addressed; and believes that there is merit in exploring the introduction of problem-solving justice in Northern Ireland as an innovative and effective approach to the criminal justice system, particularly against a backdrop of increased budgetary pressure in the public sector.

In this new Mandate, the issue of problem-solving courts continues to be a key priority area for the Justice Committee.

The Draft Programme for Government 2016-21 contains, under Outcome 7, the following statement:

We will progress a “Problem-Solving Justice” approach, looking beneath offending behaviours to identify and tackle underlying factors contributing to offending. By addressing the causes of offending behaviour we will set those at risk of future offending on different life trajectories, to their advantage and to the improved safety of our community.

Further on in the document, it is stated more specifically that this approach will include ‘running a pilot of a substance misuse court and a family drug and alcohol court’.