Piecing together a budget is one of the most fundamental activities of government. But in Northern Ireland (NI) there is currently neither a government nor a budget for the next financial year. Fresh elections have just returned a smaller number of MLAs to the Assembly. Even if a new Executive is now formed incredibly quickly, it is likely to be hard pushed to build a budget and get it approved before 31 March.

The word budget entered English in the fifteenth century, meaning ‘pouch, wallet, or bag’. In modern usage, however, a budget is essentially an estimation of the revenue and expenses over a specified future period of time. In public expenditure terms, it’s how governments plan to raise and spend tax revenue.

So what happens in Northern Ireland on 1 April, the start of the new financial year? Will departments have the money they need to pay for public services?

The quick answer to this is ‘yes’, in the short term. In the absence of a politically agreed budget, the Northern Ireland Act 1998 allows an official (i.e. the Permanent Secretary of the Department of Finance, DoF) to issue money to departments. In the longer term, it becomes a little more complicated. This blog post seeks to explain some of the issues.

How is the Executive’s budget normally agreed?

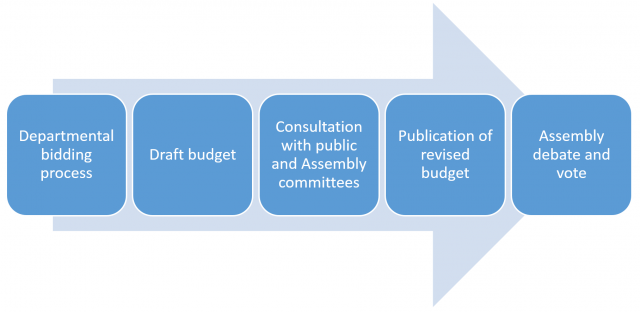

Until 2015-16, the NI budget was set for a number of years using this process:

Because of political developments, however, these stages did not occur for the coming financial year. With no agreed budget for 2017-18, the Assembly was dissolved on 26 January 2017 ahead of elections on 2 March. This means that the Assembly hasn’t provided legal authority for government departments to spend money from 1 April 2017.

Fortunately for those people depending upon public services, section 59 the Northern Ireland Act 1998 allows the Department of Finance (DoF) Permanent Secretary to:

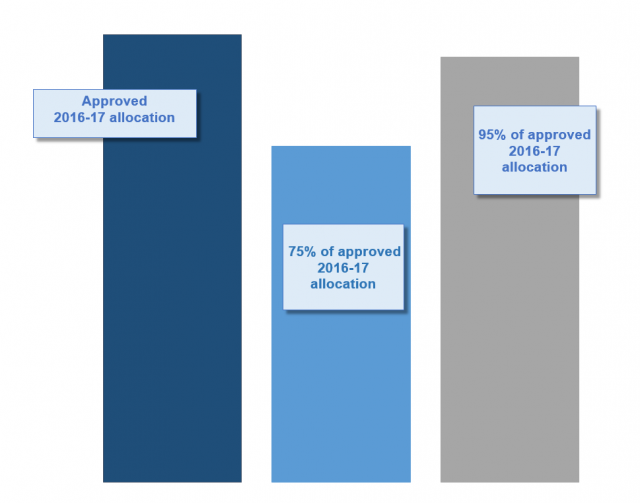

1. issue up to 75% of the 2016-17 approved expenditure if no budget is in place on 29 March 2017; and,

2. issue up to 95% of the 2016-17 approved expenditure if no budget is in place by the end of July 2017.

The timetable for the newly elected Assembly to form a new Executive and pass a budget looks extremely tight, so it seems likely that the DoF Permanent Secretary will have to exercise the reserve powers in the meantime. But the powers are not without drawbacks.

The dark blue column shows the total amount of resources approved by the Assembly for 2016-17 – i.e. the current year. The light blue column shows the 75% that the DoF Permanent Secretary may authorise for departments to spend in 2017-18, assuming he has to exercise the section 59 powers in March 2017. The grey column shows the 95% that the DoF Permanent Secretary may authorise for departments to spend in 2017-18, assuming he has to exercise the section 59 powers in July 2017.

How will the section 59 powers work?

To date, no permanent secretary has exercised the section 59 powers. In an evidence session at the Committee for Finance on 16 January 2017, the DoF Permanent Secretary said:

It will be difficult to determine what the allocations to various departments should be.

He explained he would apply:

…a largely arithmetical approach […] in consultation with my permanent secretary colleagues.

The aim would be:

…to ensure […] as far as possible [that] departments got what they needed to ensure that public services were maintained as optimally as possible.

Ultimately, even with this stopgap measure, it would reach a point where the cash runs out if a budget is not agreed. It is quite obvious that the third column is smaller than the first column, meaning 95% of the current year’s budget is unlikely to be sufficient for the next year, particularly once inflation is taken into account.

Why have the 75% and 95% limits in the Northern Ireland Act 1998?

When the Bill was under consideration in Westminster in 1998, the Northern Ireland Office produced a set of explanatory ‘Note on Clauses’. These give an indication of what the government at the time intended the legislation to achieve.

In relation to what became section 59 of the NI Act 1998, the Notes on Clauses[1] state that 95%:

…will almost certainly fall considerably short of the sums required…

This might initially seem strange. Why would the government draw up legislation that would not grant sufficient money?

Later, a hint is provided. The Notes explain that the shortfall:

…provides an incentive to the Assembly to reach agreement.

It appears therefore, that the 1998 UK Government intended the legislation to provide a carrot-and-stick incentive to the Assembly to compromise over budgetary decisions.

Indeed, during Committee Stage, the House of Lords considered (though ultimately rejected) an amendment to set the initial limit at 50% in place of 75%. This was intended to create “an even stronger incentive” for the Assembly to agree a budget.

Whether the incentive will transpire to be sufficiently strong is yet to be seen. In the meantime, another issue to consider is a difficulty arising from departmental income, known as ‘Accruing Resources’. This is income received by a department which it is authorised to retain to offset related expenditure.

Authorisation to spend Accruing Resources

In normal circumstances, after the Assembly has approved the expenditure set out in a budget, the DoF will lay a minute in the Assembly which directs departments on the use of Accruing Resources. This minute isn’t published, but the figures are included in the Estimates Documents.

The 2016-17 version states that the Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs, for example, may spend income arising from:

…recoupment of salaries and associated costs for seconded staff; European Union (EU) income; receipts in respect of various goods and services provided by the Department; receipts in respect of leases; miscellaneous licence fees; recoupment from other departments/agencies for various services provided by the Department; receipts in respect of Carrier Bag Levy; sale of timber; the forest estate; salvage of livestock slaughtered under the disease eradication programme and sundry income

As well as specifying the usage of the income, the DoF minute also sets a limit. In the case of DAERA for 2016-17, this limit is over £300 million.

Without a budget, or the DoF minute, the Accruing Resources cannot be spent by departments. As the DAERA example shows, the sums can be very significant.

Domestic and non-domestic rates

In the evidence session at the Committee for Finance on 16 January 2017, the DoF Permanent Secretary also explained that without an agreed budget, the Executive cannot issue rates bills.

This has two key implications:

1. The regional rate will not be collected, and therefore cannot be used to fund services delivered by government departments; and

2. The district rate will not be collected, and therefore cannot be used to fund services delivered by councils.

Again, in the short term, the DoF Permanent Secretary said:

…even if we are not collecting the rates, we will be able to draw down sufficient cash […] to meet […] payments to Departments, plus the expectations that councils will have for district rate revenue.

How can these problems be resolved?

In the evidence session at the Committee for Finance on 16 January 2017, the DoF Permanent Secretary emphasised that the s.59 procedures were intended to be a short-term measure or ‘stopgap’ to ensure the continuity of public service delivery.

Because of the resource constraints resulting from the combination of the 95% of 2016-17 appropriations, the inability to use Accruing Resources, or issue rates bills, some form of resolution will be required.

Following the election, a new Executive’s top priority would likely be to agree a budget. After that, it would be for the Assembly to approve or reject it. After a budget is agreed, a Budget Act will also be subsequently needed. If this happens, the need to rely on section 59 allocations will cease, allowing departments to make plans with some degree of certainty.

If no Executive is formed there has been speculation that direct rule from Westminster could be reintroduced.

In the evidence session at the Committee for Finance on 16 January 2017, the DoF Permanent Secretary said:

…if there were to be direct rule, a direct rule Secretary of State (SoS) would, we have to assume, take upon himself the same powers as the Executive would have.

In other words, the SoS would produce a budget and introduce legislation in Westminster to authorise expenditure by Northern Ireland departments. In the 1990s, prior to the Good Friday/Belfast Agreement, such authorisation was undertaken by the UK Parliament following presentation of estimates by the Chief Secretary to the Treasury.[2]

One way or another, it’s necessary that a budget for 2017-18 is agreed. Whether that will be by the Assembly or some other means remains to be seen.

[1] Northern Ireland Office (1998) ‘Northern Ireland Bill: Notes on Clauses’, see Clause 47

[2] Birrel, D (2009) ‘Direct rule and the governance of Norther Ireland’ Manchester University Press, Manchester, see page 153