By Lesley-Ann Black and Keara McKay

This article is an updated version of a piece which was published on Research Matters in February 2019. It includes statistics updated with 2018 figures, a revised distribution map, and commentary on the Protect Life 2 Strategy which was published recently.

Suicide is a major public health issue which devastates families and communities. Almost every day in Northern Ireland a person takes their own life. The circumstances that may lead a person to take their own life are complex and unique. Ascertaining why a person may end their life through suicide is still poorly understood.

Thoughts of suicide or suicidal behaviour may be triggered by a single event or, a series of events over time. Risk factors, such as self-harm and mental illness (treated or untreated) are also linked to suicidal behaviour. Suicide can also be related to a complex interplay of life problems of a personal, social or economic nature which can lead to feelings of hopelessness and despair, such as:

| Drug / alcohol misuse |

| Family history of suicide |

| Trauma or abuse |

| Unemployment |

| Social isolation |

| Poverty |

| Poor social conditions or homelessness |

| Imprisonment |

| Violence |

| Family breakdown |

| A previous suicide attempt |

| Chronic disease or disability |

There are many challenges regarding the mental health and wellbeing of the local population, not least that Northern Ireland is a post conflict society. People here experience 20-25% higher levels of mental health illness when compared to the rest of the UK, and around 1 in 5 adults are reported to have a diagnosable mental health condition at any given time. There are significantly higher levels of depression than in the rest of the UK, higher antidepressant prescription rates, and higher incidences of self-harm. Northern Ireland also has the highest rate of suicide in the UK. These are all indicators of poor mental health.

The proportion of spend on mental health remains the lowest in the UK; estimated at around 8% of the total healthcare budget, despite the evidence of the substantial levels of need. Overall expenditure on mental health in Northern Ireland remains unknown, as mental health funding is allocated across different programmes of care and the Health and Social Care Board.

Statistics

The Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency (NISRA) produces statistical data on suicide deaths. This article uses NISRA data and updates the latest annual published figures available for 2018.

Suicides are officially recorded according to a UK-wide definition. This includes deaths from Self-inflicted Injury as well as Events of Undetermined Intent. The definitions are linked to a series of standardised International Statistical Classification of Diseases codes (ICD10) which are used for tabulating cause-of-death mortality statistics.

However, care should be taken when interpreting suicide data. Firstly, suicide rates are likely to be higher than the figures reported because anomalies and underreporting in the classification of suicide deaths exists. Secondly, the registration of a death can be delayed where accidental, unexpected or suspicious circumstances arise. Suspected suicide deaths are likely to be investigated by the Coroner Service in Northern Ireland. This can result in a delay from when the death occurred to when it is officially registered – which may not be in the same year. Although the centralisation of Northern Irelands’ Coroners Service in 2006 has reduced delays, registration can still take many months. For example, the average time taken to register a death by suicide was 328 days in 2006 and 168 days in 2018.

Significant differences also exist in the coronial, inquest and registration processes in how suicide data is collected and interpreted across the UK. Despite this, Northern Ireland still has the highest age standardised suicide rate per 100,000 population compared to other UK jurisdictions. In 2018, Northern Ireland had a rate of 18.6 per 100,000 people, which is a slight increase on 2017 figures, whereas England’s rate was nearly half that at 10.3 per 100,000 people. The rate per 100,000 people in each UK jurisdiction for 2017 and 2018 is presented in Table 1.

| Jurisdiction | Rate per 100,000 in 2017 | Rate per 100,000 in 2018 |

| England | 9.2 | 10.3 |

| Wales | 13.2 | 12.8 |

| Scotland | 13.9 | 16.1 |

| Northern Ireland | 18.5 | 18.6 |

Table 1: Age standardised suicide rate per 100,000 in UK jurisdictions (2017 and 2018)

Northern Ireland: Statistics by year

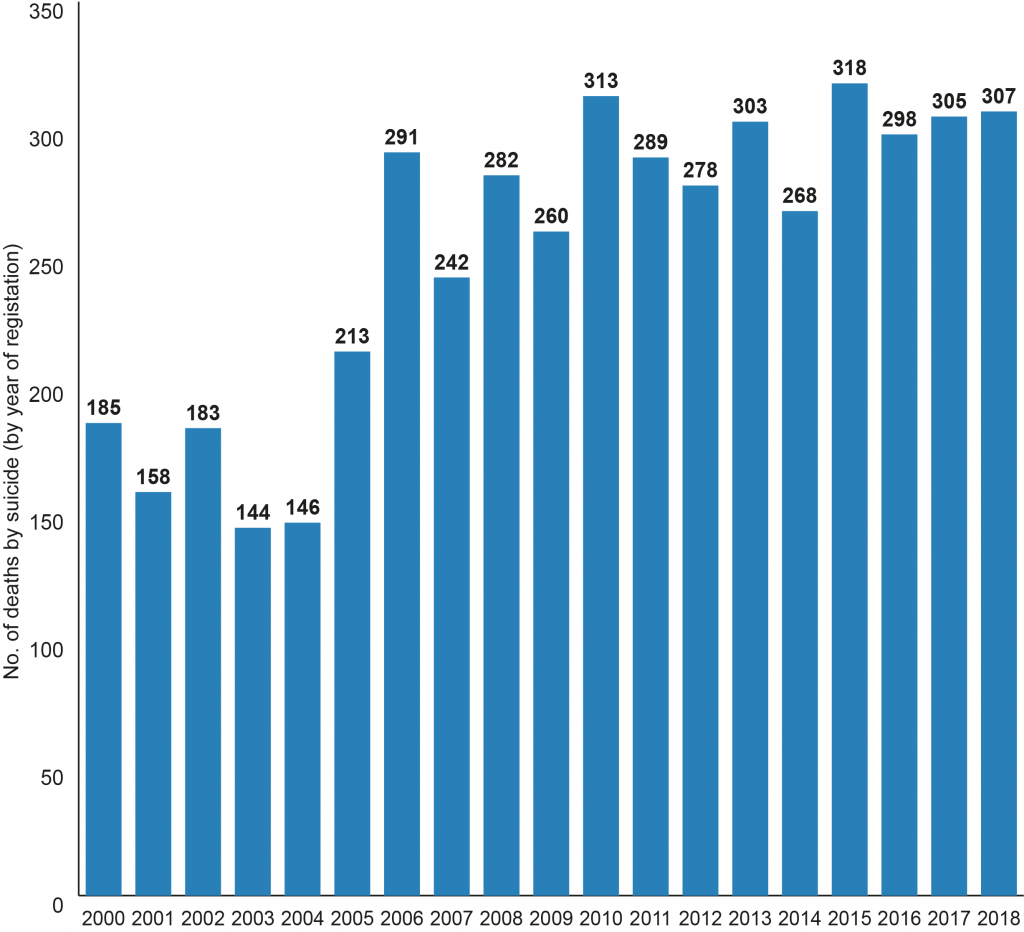

Between 2000 and 2018, a total of 4,783 deaths were registered as suicide in Northern Ireland (Figure 1). In 2000, 185 deaths by suicide were registered. By 2005, the number rose to 213. In 2018, the number of registered deaths from suicide was 307 (this is the third highest annual rate since 1970 when suicide rates began to be reported, almost 50 years ago).

Whilst it is not always possible to know why someone may end their life with suicide, several possible explanations have been offered as to why Northern Ireland is experiencing these high population rates. These are related to: the need for increased mental health service provision, rising drug and alcohol misuse, changes in family life and normative expectations, the recession, unemployment, and the legacy of the conflict.

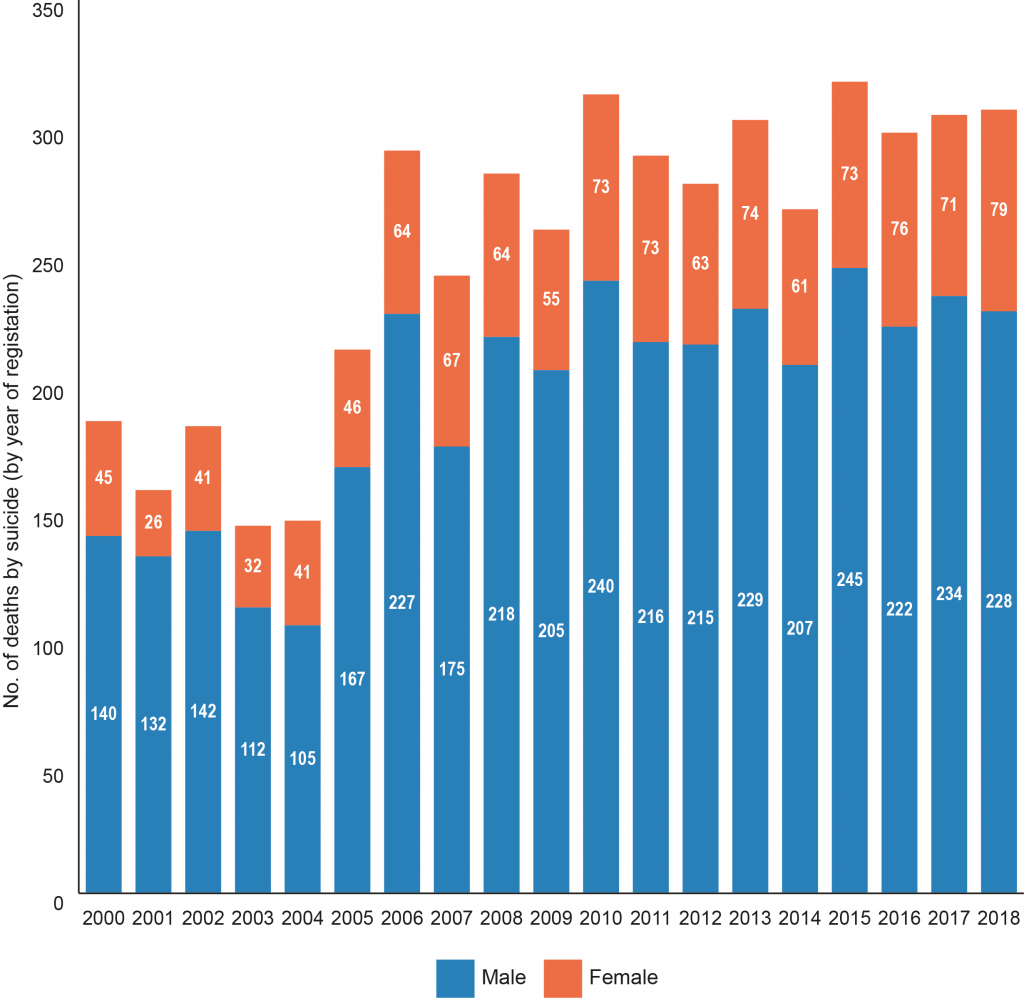

Figure 2 provides the number of deaths by suicide by gender between 2000 and 2018. In that timeframe death by suicide increased substantially, 43% for females and 63% for males respectively.

Although females are more likely to self-harm and attempt suicide, men are three times more likely to die by suicide. Studies have been conducted to ascertain the increased risk of male suicide and why they are such a hard-to-reach group. Reasons may include the perceived stigma attached to discussing mental health problems and a reluctance to seek support, higher rates of substance misuse, impulsivity and access to more lethal methods of suicide, as well as ‘at risk’ groups (gay, transgender, ethnic minorities, farmers, unemployed, rurally isolated, and divorced or separated males).

Geography

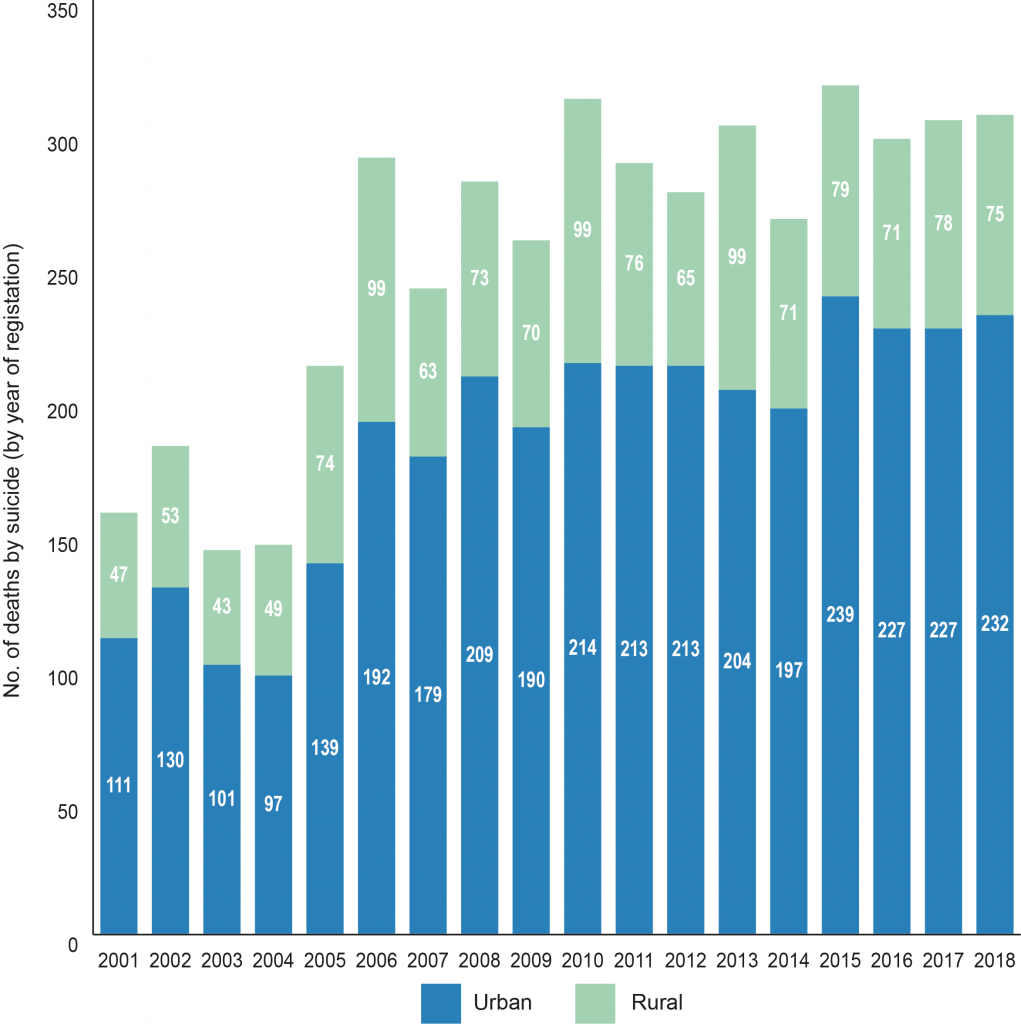

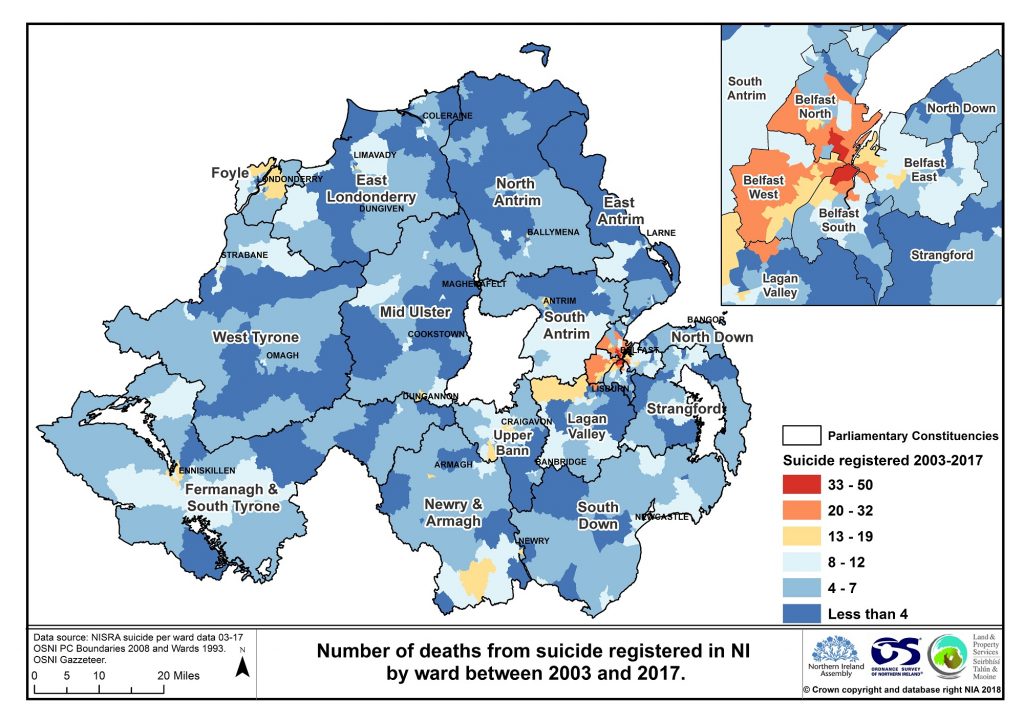

Suicide rates also vary by geographical area. Two-thirds of the local population live in urban areas, where suicides are more likely to occur (Figure 3). However, importantly, urban and rural populations can differ in a number of ways, for example in terms of attitudes, community cohesion, mental health status, and accessibility to services and facilities.

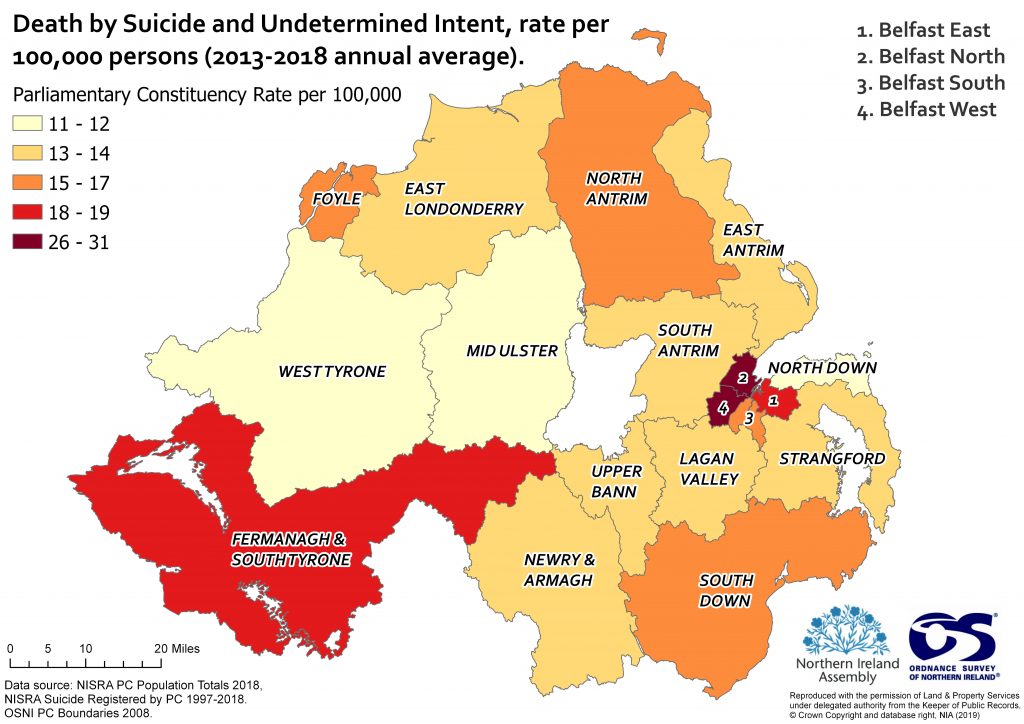

Map 1 shows the average rate of suicide per 100,000 persons by parliamentary constituency over a five-year timeframe from 2013 to 2018.

The constituencies with the highest average annual suicide rates over the five-year period are:

- Belfast North (31 per 100,000);

- Belfast West (26 per 100,000) and

- Fermanagh and South Tyrone (19 per 100,000).

Both Belfast North and Belfast West are small urban geographical areas with dense populations, whereas Fermanagh and South Tyrone is a much larger geographical area, with a slightly larger and more rural population. The data also shows that the number of registered suicides has increased in North Belfast from 26 in 2017, to 40 in 2018. It must also be noted that North Belfast had the highest number of registered suicides in 2016, with 43; this is also the highest number for any constituency between 1997-2018.

Map 2 shows the level of suicide at ward level between 2003 and 2017. Higher incidents of suicide are depicted in yellow, orange and red colours, while blue colours illustrate lower rates of suicide. As can be seen, the highest rates (shown in red) are linked to urban areas across Northern Ireland, specifically in Belfast. Between 2003-2018 three wards in Belfast had more than 40 deaths by suicide reported (Waterworks, Shaftesbury and New Lodge); the Super Output Areas within these wards are ranked within the top 20% most deprived in Northern Ireland. 24 wards reported at least 20 or more suicides, all of which were located in urban areas. Ten wards had no registered suicides in the timeframe, but all other wards had at least one suicide reported.

There is still a lack of understanding as to why there is such a difference between urban-rural suicide rates in Northern Ireland. Part of the reason may stem from deprivation. Life expectancy and health outcomes for people in deprived areas are significantly less than more affluent areas, and the suicide rate is around 70% higher in deprived areas than non-deprived areas.

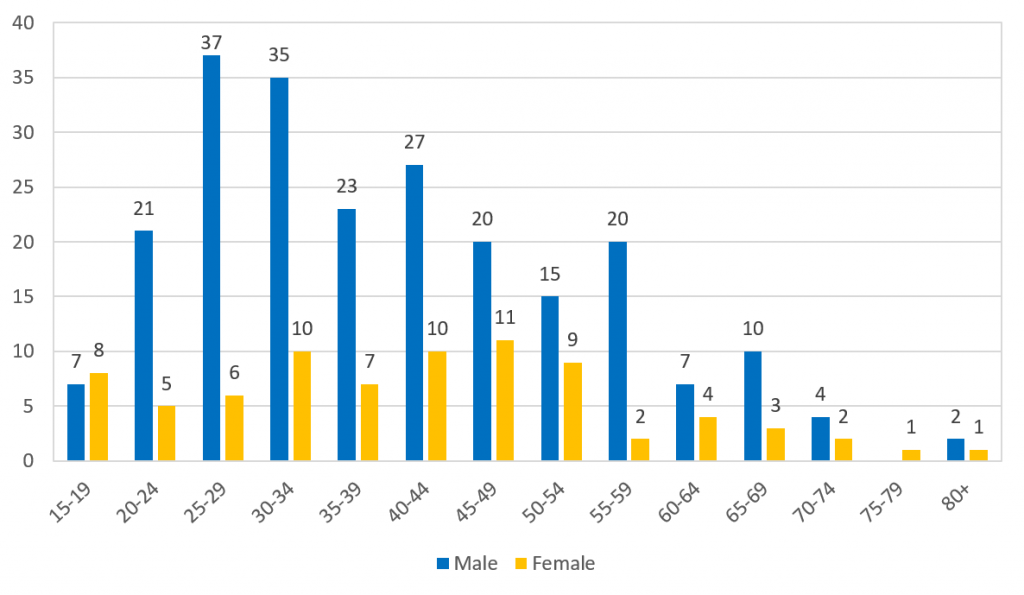

Age

In men under 50, suicide is the leading cause of death in the UK. In 2018, the highest number of male deaths by suicide in Northern Ireland occurred in the 25-29 age group (37 deaths) and 30-34 age group (35 deaths). The 45-49 age group experienced the highest deaths for females (11 deaths).

Figure 4 shows the breakdown of registered suicides by age group and gender in Northern Ireland in 2018.

Suicide is also affecting more young people – rates in the under 18s are disproportionately higher here compared to the rest of the UK. Stressors which might contribute are linked to academic performance, body image, peer pressure, and social media to name but a few. Furthermore, a National Inquiry revealed a significantly higher percentage of young people who died by suicide from Northern Ireland had a history of alcohol / drug misuse when compared to England, Scotland or Wales.

Suicide Strategies: developments

According to the Department of Health (Northern Ireland), suicide and mental health remain key policy priorities. Whilst difficult to predict, with appropriate support, it has been suggested that many suicides are preventable.

A timeline of departmental suicide prevention strategies in Northern Ireland are shown below.

| Timeline Strategy / plan name | |

| 2006-2011 | Protect Life 1: Northern Ireland Suicide Prevention Strategy and Action Plan |

| 2012 | Evaluation of NI Protect Life 1 Strategy and Action Plan |

| 2012-2014 | Refreshed Protect Life: A shared vision. The Northern Ireland Suicide Prevention Strategy |

| 2012-2014 | Refreshed Protect Life: Action Plan |

| 2016 | Protect Life 2: A draft strategy for suicide prevention in the north of Ireland |

| 2019-2024 | Protect Life 2 – A Strategy for preventing suicide and self- harm in Northern Ireland |

Table 2: A timeline of departmental suicide prevention strategies in Northern Ireland

In 2006 the first suicide strategy for Northern Ireland called Protect Life 1, was published. Its aim was to reduce the suicide rate in Northern Ireland. An overall target to reduce suicides by 15% by 2011 was set. This was not achieved.

The strategy also contained eight objectives and 62 actions to be delivered with involvement from government departments and agencies. Actions focussed on themes such as self-harm, communities, children, media and coroner reporting.

In 2012, accountancy firm Moore Stephens evaluated the strategy. It concluded that progress and examples of good work had been made in some areas. Nevertheless, much more work was required. 18 recommendations were also made, including:

- better governance and accountability for oversight and delivery of the strategy;

- ongoing involvement and support for community and voluntary sectors and greater involvement of Government Departments;

- development of a robust monitoring and evaluation framework;

- more effective tracking of resources.

The evaluation reported that progress against the 62 actions was variable. A number of issues were highlighted – some actions were difficult to measure and those requiring cross departmental or interagency working experienced the least progress. The evaluation noted that the Refreshed Protect Life Strategy (2012- 2014) would see a reduction in the number of actions to 50, and 10 new actions added into an Action Plan. However, the authors of the evaluation suggested there were still too many actions; and that these should be reduced and reclassified to afford greater focus.

The Refreshed Protect Life Strategy (A Shared Vision) was published in 2012. Although a reduction in the suicide rate remained the main goal, a new aim, ‘to reduce the differential in the suicide rate between deprived and non-deprived areas’ was added. The strategy also included 6 measurable objectives and 4 further longer term objectives with success indicators for monitoring purposes. The strategy highlighted that progress had been made in several areas such as: the establishment of the Lifeline 24/7 crisis response helpline, awareness raising public information campaigns, training programmes, and the development of community-based suicide prevention initiatives. But, it also acknowledged that more needed to be done to tackle suicide.

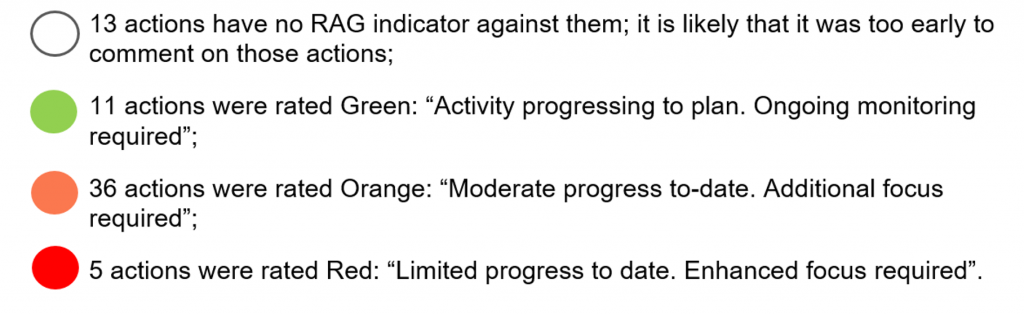

Alongside the refreshed strategy, a refreshed Action Plan (2012-2014) was published which included a red, amber and green (RAG) status report of progress on the actions. These are summarised as:

The refreshed strategy (2012-2014) actually remained in place until the new Protect Life 2 strategy was published in 2019. However the Department of Health (Northern Ireland), confirmed that no updated progress on the actions was published. Therefore, it has not been possible to accurately assess the refreshed strategy’s impact or effectiveness against the 65 actions listed in the figure above over the last number of years.

In 2016, a draft strategy was consulted upon for what would later become Protect Life 2. It highlighted many ongoing initiatives in terms of prevention, and contained ten objectives, again linked to high level actions. However, the public consultation analysis on the draft strategy suggested that there were too many actions and that any forthcoming suicide prevention strategy should seek to:

- increase funding;

- set a target in line with WHO 10% reduction in the suicide rate;

- create measures to assist with implementation and evaluation;

- develop a training plan across all sectors;

- have more focus on the 72% of people not known to mental health services;

- provide more focus on children and young people; and

- give greater emphasis on the impact of alcohol and drugs.

For the purposes of this blog article, correspondence with the Department of Health in 2018 reiterated the draft suicide prevention strategy for Northern Ireland had not been implemented – given the absence of Ministerial approval and a functioning Executive. Yet, three years after the original consultation, and still without a Minister or Executive in place, the Department of Health published the Protect Life 2 (2019-2024) strategy in September 2019.

This latest five year strategy has two main aims, namely to:

- Reduce the suicide rate in Northern Ireland by 10% by 2024.

- Ensure suicide prevention services and support are delivered appropriately in deprived areas where suicide and self-harm rates are highest.

The strategy sets out 10 objectives and 44 actions which the strategy posits will require co-operation from a range of Government departments, agencies, and sectors. In addition to the £8.7 million invested annually in suicide prevention, a further £1.3 million has been made available in 2019/20 through the Transformation Programme for Protect Life 2 initiatives (relating to suicide prevention and emotional health and wellbeing). A more detailed implementation plan with associated indicators of progress is awaited from the Public Health Agency. It is also envisaged that a new Strategy Steering Group will be established to drive forward the actions and report on performance and progress.

As it stands at present, it remains unknown exactly how these latest actions will be measured and what impact this new strategy will have on reducing the high rate of suicide experienced in Northern Ireland.