This blog article examines the similarities and differences between the planning systems north and south of the border on the island of Ireland. It is based on a more detailed research paper prepared jointly by the Northern Ireland Assembly Research and Information Service (RaISe) and the Oireachtas Library & Research Service, with contributions from research staff working for each of the two legislatures. The paper – A comparison of the planning systems in Ireland and Northern Ireland – describes and compares aspects of the current land use planning systems operating in Northern Ireland (NI) and the Republic of Ireland (RoI) and how both systems differ from one another. It also explores some considerations around the impacts of Brexit and the two planning systems, particularly in relation to the border region.

Both NI and RoI operate under a two-tier planning system with planning responsibilities split between central government and local councils/planning authorities. Both planning systems are ‘plan-led’ meaning that planning decisions are made based on national and local development plans and policies. These work to provide a balance between development and environmental protection, while ensuring the needs and well-being of local communities are provided for. Both jurisdictions allow for certain types of permitted (known as ‘exempt’ in RoI) development that do not require a planning application, this includes change of use within the same ‘use classes’ as defined in the respective pieces of legislation. Unauthorised development or breaches of planning consent are dealt with by each jurisdiction under their system of enforcement, operated by the local council/planning authorities.

Similarities and differences

While the basic structures of the two systems are similar, there are differences in the detail and in how each system works. The paper does not intend to provide a complete like-for-like analysis of both systems, but highlights some of the main similarities and differences. These include the following:

- Both systems operate a slightly different planning policy hierarchy, with more tiers in RoI than in NI.

- In NI and RoI, local planning authorities produce development plans for the whole council area, and more localised plans for site specific areas within the council boundary. The difference being that all councils in NI must produce Local Policies Plans as part of the overall local development plan (LDP) process, whereas in RoI, local councils must only produce their more specific Local Area Plans if the population is greater than 5000.

- NI operates a scheme of delegation under Section 31 of the Planning Act 2011. This allows for certain local applications to be dealt with by local authority officers instead of the planning committee. However, RoI does not have a similar system in operation.

- Nationally significant projects are decided differently between the two jurisdictions; where in RoI they go to An Bord Pleanála (the planning appeals body), and in NI the Department for Infrastructure.

- The appeal process in RoI allows for third party appeals, while NI does not.

- Both NI and RoI have provisions for developer contributions in relation to necessary infrastructure works and mitigation measures. These might include the construction of local facilities including schools, roads, community centres, or visual screening through the planting of trees etc. However, the difference is that NI does not provide for developer contributions for social housing, whereas RoI does. The issue has been discussed in NI through consultation and research. The latest position from the Minister for Communities in 2016 is that:

Independent research, published by the then Department for Social Development in February 2016, highlights that most housing markets in Northern Ireland could not sustain a scheme of developer contributions at present.

As discussions continue around Brexit, the impacts it may have on NI and its border with RoI has been one of the main areas of focus. While NI and RoI operate under different planning systems, both systems have been influenced by developments in the EU, particularly around areas such as spatial planning, environmental requirements and enforcement. This article will explore these themes now in a little more detail.

Spatial planning

The European Spatial Development Perspective (ESDP) is a non-binding statutory agreement by Member States to follow common objectives for spatial development within Europe. It was formally adopted by the EU in May 1999, and focuses on the role of spatial planning, investment and infrastructure for the development of remote border communities. With this in mind, overarching spatial strategies both sides of the border, the Regional Development Strategy (RDS) 2035 and the Project Ireland 2040 – National Planning Framework in Ireland (NPF), make reference to the ESDP. This includes the need for co-operation both sides of the border in order to encourage development.

Environmental requirements

Planning is informed and influenced greatly by environmental requirements, which are currently driven by EU legislation. For example, the Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) and the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) directives set out environmental assessment requirements for plans and projects, so as to protect, or mitigate some of the impacts for, species and habitats from development.

The European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018 aims to copy over all environmental EU law into domestic law from the day of exit. The draft Withdrawal Agreement makes provision for a Protocol on RoI/NI which includes continued north-south co-operation in a number of areas, including the environment.

Post Brexit, environmental requirements may continue to have a direct impact on planning and planning decisions in the border region. However, it is not yet clear what direction will be taken with new environmental legislation and policy in the UK and NI, and whether there will be much difference with RoI in the longer term. Any divergence could affect cross border development if businesses wishing to work in the area have to understand and adhere to two potentially different regulatory frameworks. Even more so, it is not clear how much say NI will have over setting its own agendas in certain environmental areas.

Enforcement

While it is unclear at this stage precisely what arrangements will be in place post Brexit, it seems likely that NI will no longer be subject to the enforcement mechanism and infractions of the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU). A consultation on a new UK body to hold government to account states that:

Once we leave the EU, and regardless of the nature of the future relationship we negotiate, we will no longer be a party to the EU Treaties or under the direct jurisdiction of the CJEU.

A House of Lords Select Committee report (2017) raised issues in relation to the effectiveness of legislation once it is transposed without the influence of the CJEU to hold Member States to account:

Even a direct transfer of EU environmental legislation into UK law will result in an erosion of the protections that this legislation provides. Of concern is the loss of accountability from both the European Commission … and the [CJEU].

In light of this, questions have been asked around the impacts on the future judicial review process and the introduction of a UK wide statutory body to oversee environmental law and replace the role of the European Commission and the European Court of Justice. In a statement on such a statutory body, the Environment Secretary of State also raised the following:

One of the key questions, which we will explore with the devolved administrations (DAs), is whether Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland wish to take a different or similar approach.

Continued co-operation

During the development of local council community plans, a number of common concerns and suggestions in relation to Brexit and cross border collaboration have been identified by three out of the five councils in NI running along the border region.

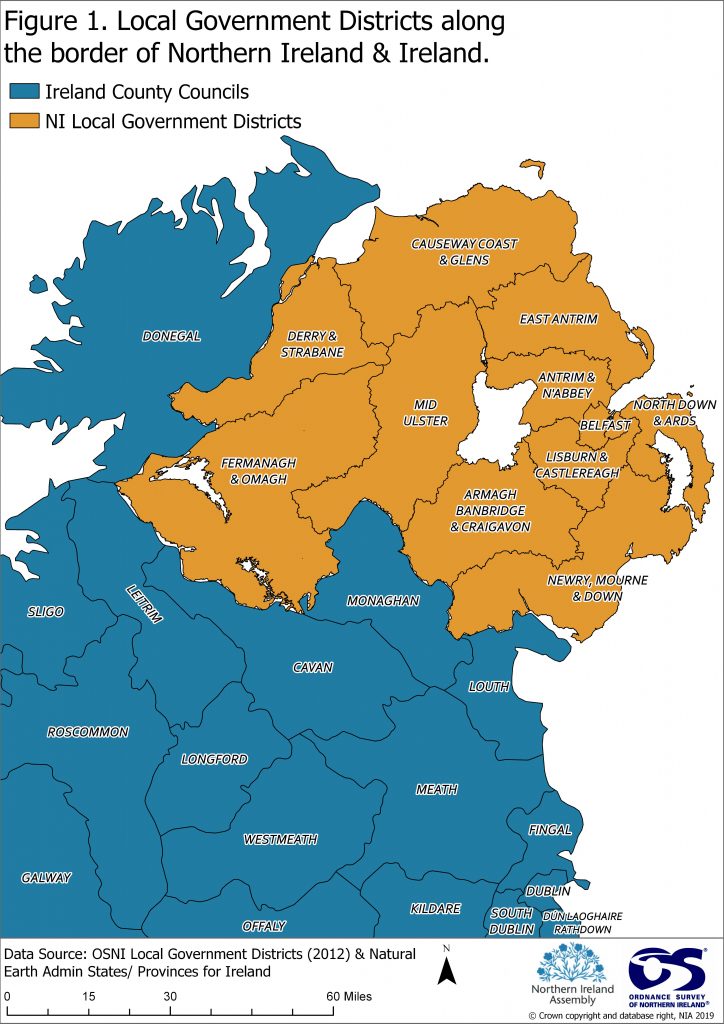

For example, as shown in Figure 1, the Fermanagh and Omagh District Council borders four counties in RoI: Donegal, Cavan, Monaghan and Leitrim. The Fermanagh and Omagh Community Plan raises concerns about the district’s border area in light of the decision to leave the EU and calls for the need for close scrutiny of the local implications. Similarly, the Mid Ulster Community Plan stresses the need to further develop cross border opportunities in the area and suggests that the council’s new planning powers may be a way of taking this forward. Similarly, the new Derry/Londonderry and Strabane Community Plan raises concerns in relation to the impacts of Brexit on cross border trade and investment and highlights the need for integrated and closer cross border planning and delivery structures.

A year ago, the House of Commons NI Affairs Committee published its report ‘The land border between Northern Ireland and Ireland’ (March 2018). The Committee stated that it recognises the importance of cross-border initiatives in improving infrastructure and public services in the border corridor. It states that North-South cooperation is currently facilitated by a shared regulatory framework and governance bodies. The Committee recommends that the Government put forward targeted proposals for how cross border cooperation in policy areas dominated by EU law will continue after the UK leaves the EU. In relation to the political situation in NI it states,

…in the event of the restoration of the Northern Ireland Executive, EU competencies could be devolved to Northern Ireland so it can balance maintaining UK wide frameworks with EU alignment for cross-border policy areas. In their continued absence, alternative means of taking decisions will have to be devised.