Last month, a new law came into force in England and Wales making upskirting a criminal offence. Upskirting involves taking a photo or video under a person’s clothes without their consent in order to capture images of their body or underwear. This is usually done with a mobile phone, making it an example of a crime that is facilitated by technology. Technology can facilitate crime in two ways: either by creating a new act, or by giving a new forum to acts already prohibited by the law. McGlynn and Rackley (2017) suggest that while acts of voyeurism or invasions of privacy are not new, the availability of smartphones has created the new phenomenon of image-based sexual harassment. Such new behaviours often cannot be prosecuted under existing criminal law, which is why specific offences are being created. For example, a bill currently going through the Oireachtas is expected to prohibit upskirting in the Republic of Ireland by reforming the law on digital communications. In the UK, as Scotland has criminalised upskirting in 2010, Northern Ireland is now the only jurisdiction to have no specific provisions in place for this offence.

Future legislators wishing to update Northern Ireland’s law on upskirting may make one of two choices: either to adopt the approach taken by other UK jurisdictions, or to develop bespoke policy measures. In both scenarios, however, there may be significant challenges. Criticism of the current laws in Great Britain suggests that they do not go far enough to protect victims, making it inadvisable to import policies that may not be fit for purpose. At the same time, the inadequacy of available data on how to define and count technology-facilitated crimes in Northern Ireland might hinder sound policy-making.

How did the law change in Great Britain?

Upskirting first became a sexual offence in Scotland in 2010, with the introduction of the Criminal Justice and Licensing (Scotland) Act. The new act expands the definition of voyeurism contained in the Sexual Offences (Scotland) Act 2009. Before this amendment, voyeurism applied only to observing or filming of a person doing ‘a private act’, making it difficult to prosecute offences that happened when the victim was simply walking down the street or using public transport. The new law includes ‘operat[ing] equipment beneath [a person’s] clothing’, but it also specifies that an act constitutes voyeurism if committed with one of two purposes:

(a) obtaining sexual gratification,

(b) humiliating, distressing or alarming [the victim].

In England and Wales, the law was changed last year following a lengthy campaign by Gina Martin, who was upskirted by a stranger at a festival. After going to the police, she was informed that no prosecution would be possible: the act had been public enough to escape the existing definition of voyeurism, but since it had not been witnessed by other members of the public, it also fell outside of the offence of outraging public decency. Westminster followed the Scottish approach, and the definition of voyeurism contained in the Sexual Offences Act 2003 was updated to include upskirting. Just like its Scottish counterpart, the new law specifies that images must be taken either for sexual gratification, or to cause distress, humiliation, or alarm to the victim.

Criticism of the current laws

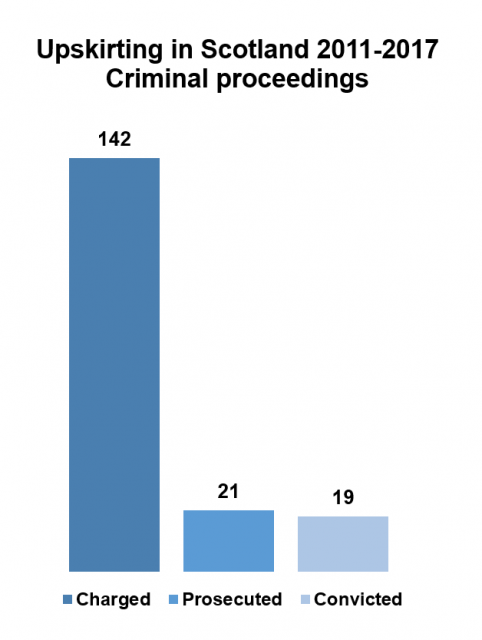

This narrow definition of the offender’s intent has proven problematic in both jurisdictions. In the first six years since the new law came into effect, 142 people were charged with upskirting offences in Scotland, but only 19 were convicted: a rate of 13% (see figure below). The difficulty of proving the nature of an offender’s intentions beyond reasonable doubt may be contributing to cases never reaching court.

In addition, the new law does not prohibit taking unauthorised intimate images for the purpose of financial gain or amusement. Images may also be taken for the purpose of being shared within a peer group, for entertainment or bonding. Sharing intimate images of a person without their consent is an offence under the Abusive Behaviour and Sexual Harm (Scotland) Act 2016, which aims to prevent revenge porn. While this offence can be prosecuted without the stringent requirements of voyeurism, it does not grant automatic anonymity to victims, which can make it less likely for them to come forward.

As the new bill was discussed in Westminster, concerns were raised over the appropriateness of following the Scottish example. The Equality and Human Rights Commission suggested the removal of the two intent requirements, or at least the addition of financial gain and entertainment. In her written evidence to the Public Bill Committee, expert in image-based abuse Professor Clare McGlynn stated that: “Sexual offences are about power and control, punishment, sexual entitlement, anger, entertainment, as well as sexual gratification”. Nevertheless, the government argued that the law should apply only to acts with an explicit sexual motive, limiting prosecution to individuals likely to go on to commit other sexual offences. This law thus does not aim to punish every instance of upskirting, but prioritises those committed by persistent sexual offenders.

Koops et al. (2018) argue that taking non-consensual intimate images is a crime against the person’s autonomy[1]. If we embrace this approach, then the law’s limited scope can be problematic from the point of view of victims’ rights. In Northern Ireland, where currently no specific law prohibits upskirting, a schoolboy was recently convicted of committing acts outraging public decency for upskirting two female teachers. Despite the successful prosecution, the case laid bare the limitations of existing law, as the focus on public decency fails to recognise the personal harm caused to the victims.

In February of 2019 the Department of Justice launched a consultation on child sexual exploitation. Here it proposed criminalising upskirting by amending the current voyeurism offence, in line with other UK jurisdictions. However, copying the restrictive intent requirements used in Great Britain could be particularly problematic in Northern Ireland, creating a noticeable loophole for images taken with the intent of being shared. Revenge porn is regulated by the Justice Act (Northern Ireland) 2016, but this only prohibits sharing images to cause distress. Circulating a person’s intimate images for the purpose of amusement would remain outside the scope of legislation, as long as the offender did not intend the victim to find out.

Measuring technology-facilitated crime

Effective policy-making requires an understanding of the problem, of who is affected, and why. Campaigners warn that image-based offences are widespread, and that people of all ages can be targeted. However, this may not be reflected in official crime statistics. This is more to do with how we count crimes than their actual prevalence. For example, a recent freedom of information request found that most police forces in England and Wales failed to provide data on upskirting, while variations in rates suggested widespread underreporting. In Scotland, where upskirting has been a crime for many years, all voyeurism offences are counted together. This not only makes it difficult to count instances of upskirting, but also to establish the characteristics of victims or the way offenders operate.

In Northern Ireland, where no upskirting law exists, the Police Service of Northern Ireland flags up offences that have an online element, which could help identify technology-facilitated crimes. However, the decision to flag offences as online crimes is taken by individual officers, and is not quality assured by the Statistics Branch. In the case of upskirting, it is unclear whether a crime would be defined as online when a smartphone camera is used to take an image that is not shared, as there would be no internet-based element to the offence.

Crime data in the UK does not only include police-recorded offences, but also national victimisation surveys. By interviewing members of the public directly, these surveys can gather data on crimes that may never have been reported to the police. This means we can gather data on technology-facilitated crimes directly from victims. For example, both the Scottish Crime & Justice Survey and the Crime Survey for England and Wales ask respondents who have been victims of crime whether the internet played a part in the offence. The Northern Ireland Safe Community Survey, however, does not mention the internet at all, focussing instead on face-to-face offences. While the questionnaire was amended in 2018 to include online offences, this only affected questions measuring respondents’ perceptions of crime rather than actual experiences of victimisation. Furthermore, the Northern Ireland survey only interviews adults, but children are particularly vulnerable to online-based offences. As a consequence, available data collection methods provide a poor insight on the prevalence or seriousness of online-based and technology-facilitated offences, particularly when they involve young people. Future policy-makers may wish to gather a clearer picture of what is going on before establishing the way forward for Northern Ireland.

———————

[1] Koops, B.J., Newell, B.C., Roberts, A., Škorvánek, I. and Galič, M. (2018) ‘The Reasonableness of Remaining Unobserved: A Comparative Analysis of Visual Surveillance and Voyeurism in Criminal Law‘. Law & Social Inquiry. 43(4): 1210-1235.