Although loneliness and social isolation are often reported synonymously, they are in fact distinct concepts. A person who is isolated may not necessarily be lonely, and conversely, it is possible to feel lonely even when surrounded by people.

For more information on this, see Age UK: Loneliness and isolation – understanding the difference and why it matters

Loneliness is a normal feeling, and one that we will all experience at some point in our lives. For many people loneliness is transient or associated with a specific event but for others the feeling of loneliness becomes chronic.

This article examines what we mean by loneliness and assesses what policy responses could be deployed to tackle its effects.

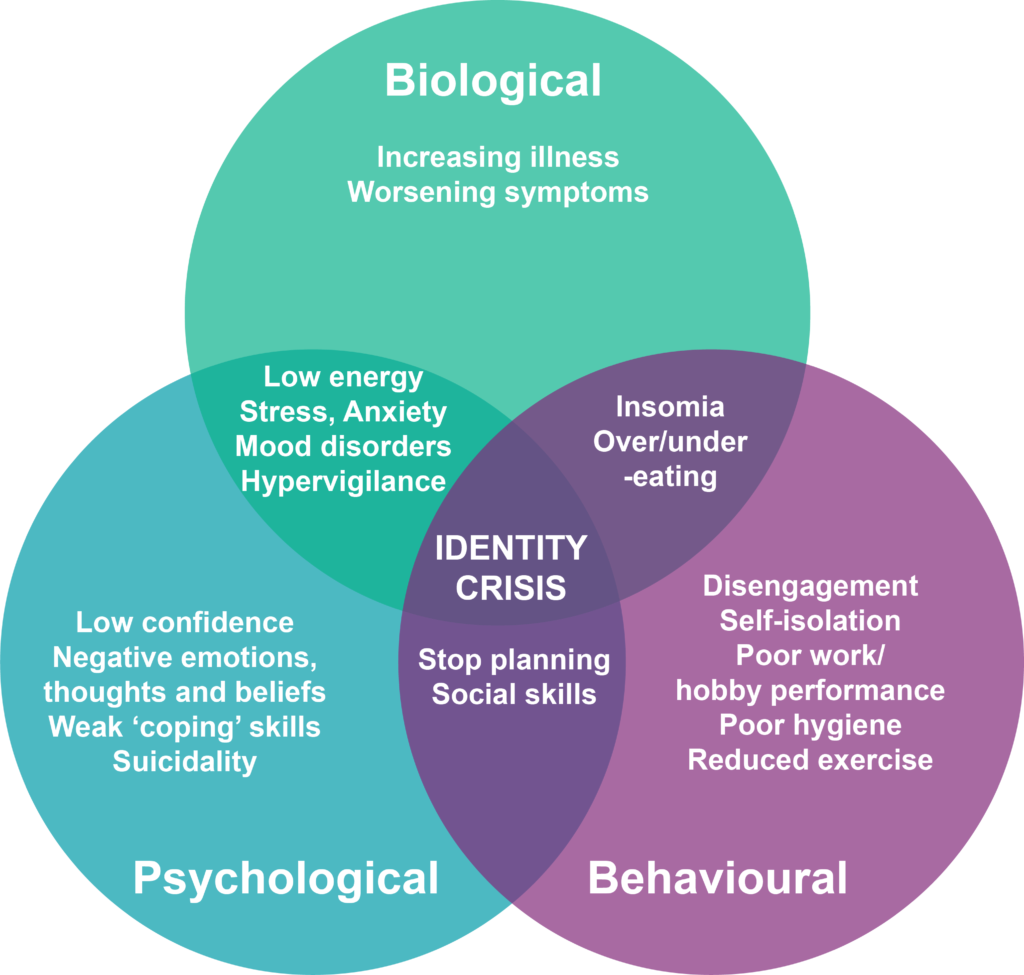

Research has demonstrated that chronic loneliness, along with social isolation, is associated with poorer mental and physical health outcomes and, consequently, is increasingly being recognised as a major public health concern. It has been claimed that chronic loneliness can be as bad for your health as smoking 15 cigarettes a day and, along with social isolation, has also been associated with increased cognitive decline, dementia, stroke and cardiovascular disease, along with a range of other conditions and illnesses.

Loneliness can also lead people to make poorer life choices, such as drinking heavily, having an unhealthy diet and exercising infrequently. Loneliness has also been linked to a reduction in sleep quality, and these factors could further contribute to the development of health issues.

As well as having a negative impact on the individual, loneliness can also be detrimental to the economy. It is estimated that the cost to employers in the UK, as a consequence of loneliness, is between £2.2 and £3.7 billion per year, according to this report by the New Economics Foundation and the Co-op.

So why do we get lonely?

Loneliness is often considered only as an issue for older people, but it is a cross-generational concern. In fact, in England, a greater percentage of younger people show signs of loneliness than those in older age groups. According to the Community Life Survey: 2018-19, 9% of those surveyed aged 16 – 24 reported feeling lonely ‘often/always’, compared to 5% of those aged 50+.

For children aged 10–15, those feeling lonely ‘often/always’ is even higher (11.3%), according to the Office for National Statistics’ Children’s and Young People’s Experiences of Loneliness: 2018 report.

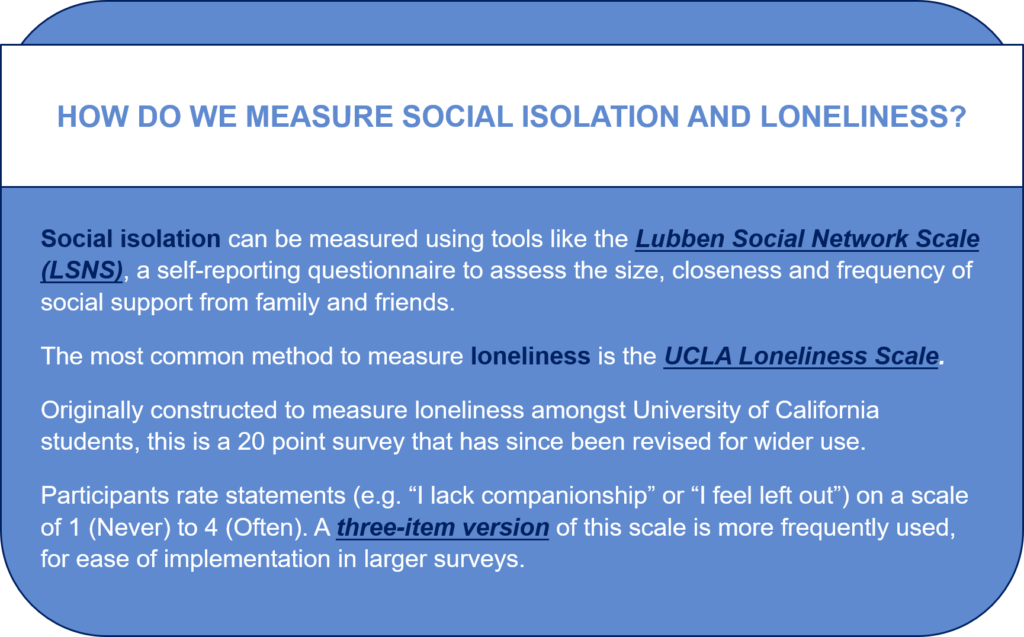

For more on this, see the Lubben Social Network Scale, the UCLA Loneliness Scale, and Hughes et al 2008.

Causes of loneliness are multifactorial and can be at individual, community or societal level, as stated in a report written for the Co-Op and British Red Cross.

For the individual, factors that can influence loneliness are usually related to health, mobility, financial security, contact with family and friends, emotional wellbeing and confidence.

Within the community this may include living in a disadvantaged area or one that experiences high crime rates, a lack of access to social activities or community services and inadequate transport infrastructure.

At a societal level, aspects of modern living can contribute to loneliness, for example: perceived social and cultural norms (e.g. not talking to strangers), the stigma attached to speaking of loneliness, the shift into a more digital society (particularly problematic for older generations who are less ‘tech-savvy’) and the impacts of austerity on local and support services.

Some of the groups that are at particular risk of loneliness are those that:

- Have a chronic illness or are living with a disability;

- Come from an ethnic or other minority background (e.g. LGBTQ+);

- Are living alone;

- Are widowed or separated/divorced;

- Have caring responsibilities;

- Are part of the Armed Forces Community;

- Are children in care, are care leavers or victims of abuse/neglect;

- Are unemployed;

- Live in a disadvantaged area;

- Feel a disconnect with their local neighbourhood.

Loneliness in Northern Ireland

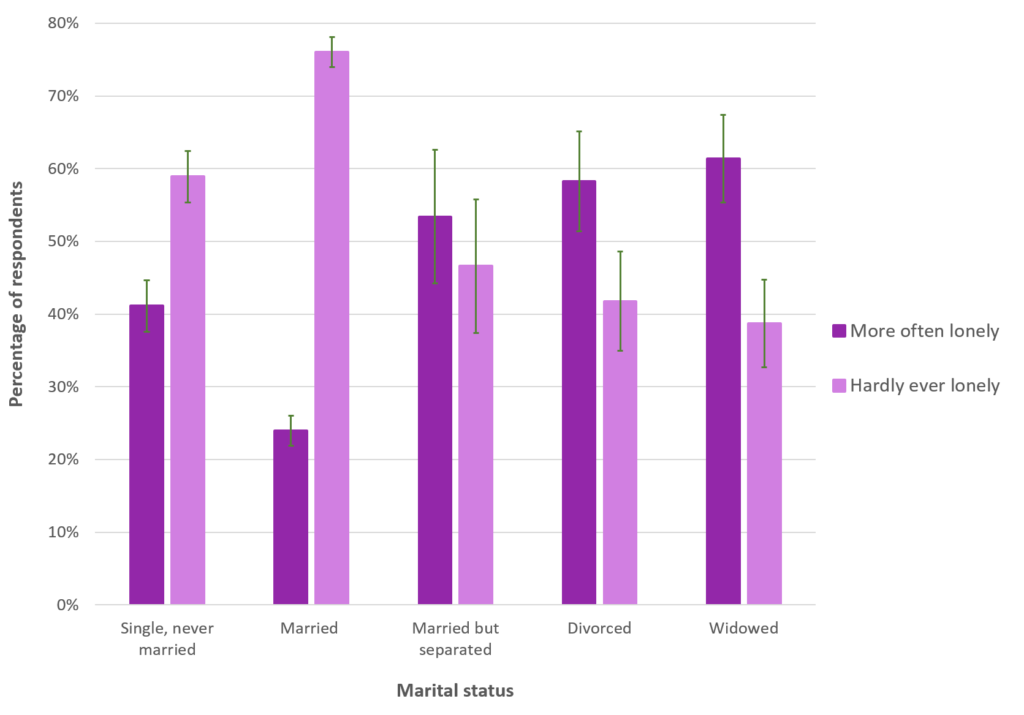

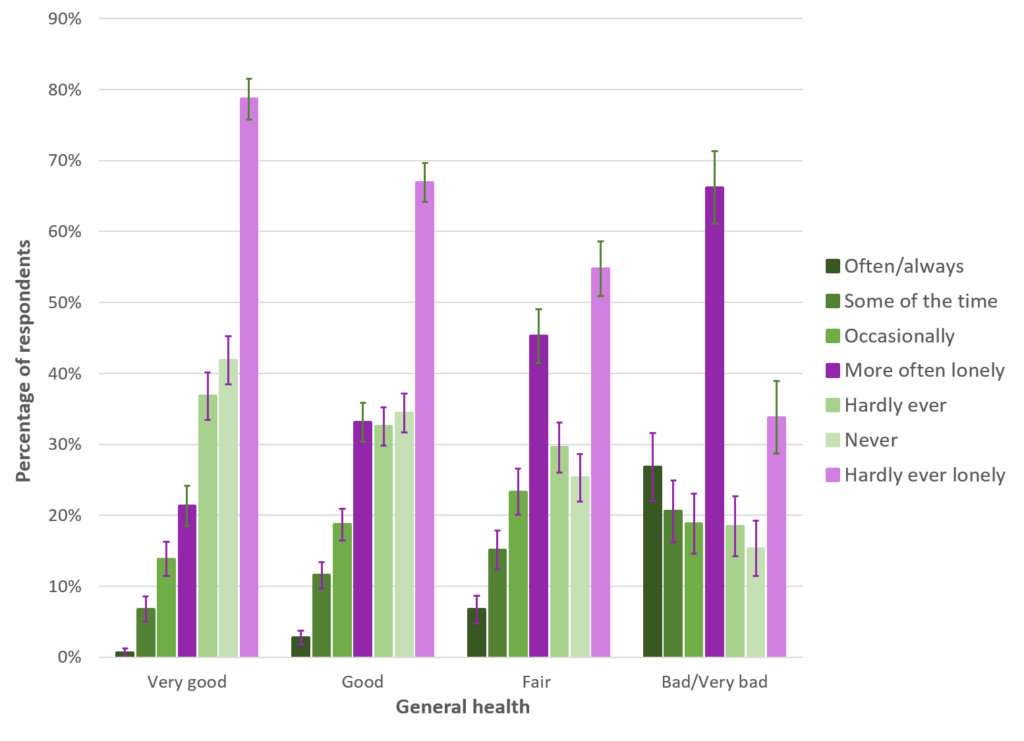

Earlier this year the Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency (NISRA) released its first report on loneliness in Northern Ireland. Just over 5% of respondents reported feeling lonely ‘often/always’, which is similar to figures in England. However, unlike for England, people over 55 report feeling lonely more frequently than those aged 16-24.

Those living in more deprived areas, those in poor health, those who are divorced or widowed and woman of all age groups, reported more frequent loneliness.

Sample sizes were small across certain categories, which makes the statistical interpretation less reliable. Because of this, NISRA re-classified those who feel lonely ‘often/always’, ‘some of the time’ and ‘occasionally’ into those who feel ‘more often lonely’. Conversely, those who feel lonely ‘hardly ever’ or ‘never’ were re-classified as ‘hardly ever lonely’.

Strategies in England

Following on from recommendations from the Jo Cox Commission report on loneliness, in October 2018, England published A connected society. A strategy for tackling loneliness: laying the foundations for change. This strategy laid out 60 commitments for the government. In January 2020 the first Loneliness Annual Report was published, with updates on those commitments.

Some of the key ones mentioned were:

- To have Social Prescribing Connector Schemes in place in local health and care systems by 2023. In line with the NHS Long Term Plan, funding has already been made available to train an additional 1000 social prescribing link workers by April 2021, with further commitments for staff training by 2023/24;

- The Home Office and Royal Mail ran a trial scheme in 2019 called Safe and Connected. This involved postal workers in selected locations checking on elderly and vulnerable residents. Partners are now reportedly looking at ways to scale-up this initiative;

- An Employer Leadership Group was set up in November 2018 to champion the Employer Pledge (committing employers to support their employee’s social wellbeing and tackle loneliness in the workplace). Over 30 businesses have already signed up, including Sainsbury’s, Transport for London, Co-op, British Red Cross, National Grid and the UK Government Civil Service;

- Community Spaces Funding – initial government funding of £1m was allocated to help tackle youth loneliness through 112 short-term projects. A further £1.6m Space to Connect Fund was set up, with 57 organisations receiving grants to ‘strengthen community spaces where people can connect and co-operate’;

- In June 2019 the Government launched the Let’s Talk Loneliness campaign, designed to raise awareness, address the stigma surrounding loneliness.

Further information on the UK Government’s Loneliness Strategy and its progress can be found in this House of Commons Library briefing paper.

Strategies in Scotland

Scotland’s strategy (December 2018), is A Connected Scotland: Our strategy for tackling social isolation and loneliness and building stronger social connections. It runs from 2018 – 2026, with progress updates promised every two years. Its four overarching priorities are:

- Empower communities and build shared ownership;

- Promote positive attitudes and tackle stigma;

- Create opportunities for people to connect;

- Support an infrastructure that fosters connections.

Some of the commitments made by the Scottish Government included:

- To set up a National Implementation Group – established in January 2019 bringing together experts, public and third sector organisations;

- To make up to £1 million available from 2018 to pilot innovative ways to tackle social isolation and loneliness – as of early 2020, this fund had yet to be used or allocated;

- By December 2019 the Scottish Government stated that they had provided an additional £140,000 to Age Scotland’s helpline, plus £80,000 to Befriending Networks; and

- Improving transport links and accessibility, particularly in rural areas and for those in later life, with funding promised to the Community Transport Association Scotland.

Strategies in Wales

Wales subsequently published its strategy in February 2020 – Connected Communities: A strategy for tackling loneliness and social isolation and building stronger social connections, with four overarching priorities:

- Increasing opportunities for people to connect;

- A community infrastructure that supports connected communities;

- Cohesive and supportive communities;

- Building awareness and promoting positive attitudes.

Commitments include:

- £1.4 million available over the next three years as a Loneliness and Social Isolation Fund;

- Promoting sport and physical activity to combat loneliness and working with organisations such as Welsh Physical Activity Partnership (WPAP) and Sport Wales to develop measures of loneliness; and

- Funding for an national Time Credits programme (involves volunteering for the community to earn credits that can then be spent on a range of activities).

And for Northern Ireland?

Although there is not yet an overarching strategy in Northern Ireland (or the Republic of Ireland for that matter), in June 2018 an Ireland-wide taskforce released a report aimed at raising awareness and informing governments and policy makers on the issues of loneliness across the island. Several government departments in Northern Ireland have strategies in place, which directly and indirectly address loneliness and social isolation, including

- The NI Concessionary Fares scheme (Department of Infrastructure), allows greater accessibility to public transport for those who are at risk of social exclusion. The Rural Transport Fund and the Transport Programme for People with Disabilities fund a number of schemes which aim to provide specialised transport options and reduce social isolation;

- The Department for Communities works with a range of its Arm’s Length Bodies to provide programmes that address social isolation and loneliness. The Department also recently committed to undertaking a scoping study on loneliness, with input from other Departments;

- The Department of Justice’s Good Morning initiative provides a daily morning call to older and vulnerable individuals who may be isolated, lonely or more at risk of experiencing crime;

- The Department of Health is undertaking scoping of existing policies/strategies to determine how issues of loneliness and isolation are being tackled. Its Protect Life strategy acknowledges loneliness as a contributor to poor mental health and it is looking at ways to develop community-support models; and

- The Department for Agriculture and Rural Development also have a framework in place to support rural communities and tackle social isolation and loneliness, through utilisation of better transport and internet networks and improving opportunities for social engagement.

Many charities and not-for-profit organisations are also working towards alleviating social isolation and loneliness in communities. For example, the Volunteer Now befriending scheme matches up volunteers with socially isolated older people.

Councils are also getting involved. In 2012, Belfast was the first city in Northern Ireland to join the World Health Organisation’s Global Network of Age-friendly Cities, and the council subsequently published their first action plan in 2014. Its most recent publication, the Age-friendly Belfast Plan 2018 – 2021, mentions several interventions that are aimed at tackling loneliness and isolation in older people.

The Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP) launched their Tackling Loneliness: A Community Action Plan in 2018, with both UK-wide and national-level recommendations. For Northern Ireland it ties into wider health and social care strategies, such as introduction of a social prescriber in all GP surgeries and better interaction between GPs and the voluntary sector.

Many organisations are pushing for Northern Ireland to follow the example set by the rest of the UK, to consult on and publish its own strategy for combatting social isolation and loneliness. Given the current situation with COVID-19 and its potential impacts on loneliness and social isolation, these issues are presently being further highlighted.