Young people have faced unprecedented changes to their childhoods and futures due to COVID-19. A significant part of this disruption has been to their education. While schools and education staff adapted admirably to online learning, several unique challenges resulting from school closures emerged. Concerns surrounding food provision for children entitled to Free School Meals (FSME), insufficient numbers of digital devices and inconsistent pupil engagement with remote learning all received significant attention from the media and stakeholders. A recent Research Matters blog article highlights how these challenges were felt more sharply by young people in Northern Ireland who are already experiencing persistent inequalities in the education system. The Equality Commission also highlighted how COVID-19 has the potential to exacerbate existing educational inequalities, both for children now and in their future.

Prior to the emergence of the current pandemic, tackling educational inequality, specifically the link between educational underachievement and socio-economic background, was already a priority for the re-established Northern Ireland Executive.

In the New Decade New Approach agreement, a requirement was set out for the establishment of an expert group:

…to examine and address links between persistent educational underachievement and socio-economic background including the long-standing issues facing working-class, Protestant boys.

The finalised expert panel, established by Education Minister Peter Weir MLA, in July 2020, has been tasked with examining these links as well as producing specific actions to address the gaps within an ambitious timescale of 10 months.

This article examines some of the factors driving educational underachievement among certain groups of students in Northern Ireland and explores current government efforts to ensure more equitable outcomes for all.

Northern Ireland’s persistent long tail of underachievement

Northern Ireland’s school system is perceived by many as high performing, with the most recent report from the Chief Inspector of the Education and Training Inspectorate highlighting how the system ‘continues to work very well for tens of thousands of learners’. However, the report also acknowledges that ‘too many students are left behind’ and there is undue variation in the quality of provision and educational outcomes for particular groups of learners.

A recent report from the Centre for Research in Educational Underachievement (CREU) at Stranmillis University College, highlighted that:

Internationally, a long tail of underachievement belies Northern Ireland’s reputation for producing academically high-achieving pupils, indicating a country level problem requiring a Northern Ireland-specific focus.

In 2018/19, 29.2% of school leavers did not achieve the benchmark of five GCSEs at grades A*-C or equivalent including English and maths. The proportion of students with FSME failing to achieve this threshold was even higher, at 50.5%. In addition, 96 boys and 62 girls left school with no GCSEs or equivalent qualifications in 2018/19.

There are also differences in the rates of underachievement according to community background. Just over a third (37.9%) of Protestant boys with FSME achieved five GCSEs at grades A*-C or equivalent including English and maths, compared to 46.7% of their Catholic counterparts. Northern Ireland also has a significantly higher proportion of 17-24 year olds who have no qualifications than the other UK countries.

Certain groups of students are more likely to underachieve

The Equality Commission identified certain groups of students who are more likely to demonstrate lower levels of academic achievement and lower levels of progression to further education:

- Males continue to have lower levels of attainment than females, beginning in primary school and continuing throughout schooling to GCSE and A Level. Fewer male school leavers enter higher education than females;

- Protestants continue to have lower levels of attainment than Catholics at GCSE and A Level. Fewer Protestant school leavers enter higher education than Catholics;

- School leavers entitled to FSM, particularly Protestants, notably Protestant males, demonstrate persistent underachievement and lack of progression to further and higher education;

- Students with Special Educational Needs or a disability also demonstrate lower attainment levels and;

- Children from the Traveller and Roma communities have some of the lowest levels of attainment of all groups.

This blog article will focus on achievement patterns related to gender and socio-economic disadvantage.

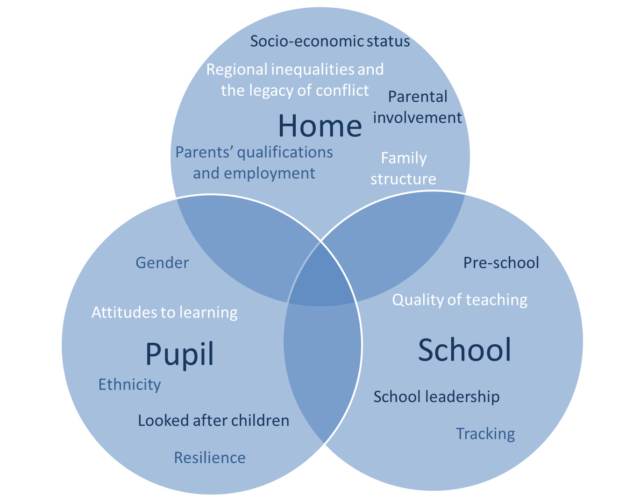

Causes of underachievement are complex and multifaceted

It is typically a combination of factors that lead to underachievement. Research suggests that around 78% of the variation in learning progress at post-primary is attributable to a student’s home and background. The remaining variation is mostly related to schooling, both primary and post-primary. Figure 1 provides an overview of the key factors contributing to underachievement.

Clearly, many of the factors that are linked to underachievement lie outside the control of schools. Nonetheless, the education system can still play an important role in mitigating against these factors, in particular socio-economic background which is a key focus of the newly established expert panel.

Relationship between socioeconomic background and underachievement is well established

Multiple international and country-specific studies have demonstrated that students from less well-off backgrounds are less likely to succeed at school. Differences between disadvantaged children and their better-off peers are evident at an early age, with children aged three, whose parents have few qualifications, already behind their peers in terms of cognitive, social and emotional development.

In addition, and often linked to socio-economic background, a number of parental factors influence children and young people’s attainment. Disadvantaged parents are less likely to engage their children in activities such as reading, painting and singing: activities that strongly promote intellectual and social development. Research found that by the age of two, there was a six month gap in the linguistic processing skills of children from advantaged and disadvantaged backgrounds.

International evidence suggests that parents who have higher levels of education and better-paid jobs have greater access to resources. These resources include:

- Financial resources: for example, computers, books and tutoring;

- Cultural resources: such as extended vocabulary and time management skills; and

- Social resources: for example, role models and networks.

A wide ranging study investigating the links between deprivation and education attainment in Northern Ireland found that young people from areas of high deprivation suffer low self-esteem and lack aspiration as a result of negative community attitudes around education. Parental early experiences of educational failure were also associated with children’s fear of failure, low expectations and negative attitudes to schooling.

Research carried out by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) indicates that student socio-economic background has a greater influence on outcomes at post-primary level in Northern Ireland than on average across other member countries.

Academic outcomes for boys, particularly disadvantaged Protestant boys, are a cause for concern

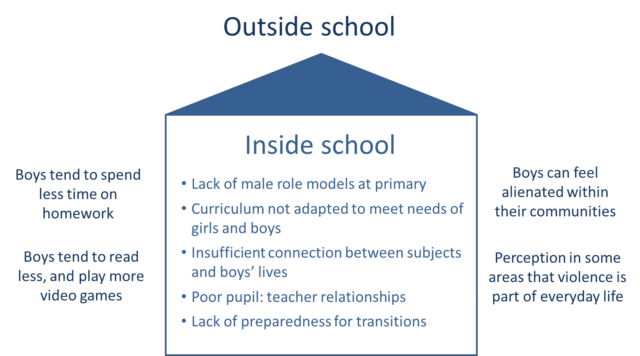

In Northern Ireland, girls tend to outperform boys at an early age and the difference widens throughout school. Evidence suggests that a complex range of factors influence boys’ achievement, and that these sit within wider contextual issues such as poverty, ethnicity, a declining industrial base and reduced demand for traditional male jobs. Figure 2 illustrates some of the key factors contributing to male underachievement.[1]

Disadvantaged Protestant boys tend to achieve significantly less well than their Catholic counterparts for several reasons including:

- The gradual decline of traditional industries in Belfast that offered employment to generations of Protestant males;

- The presence of loyalist paramilitaries in disadvantaged Protestant areas;

- Insufficient positive role models, particularly male role models; and

- A reduction in community networks of families, churches, trade unions, schools and youth groups.

Positive strides towards solving educational inequalities

The Department of Education has a wide and varied range of policies and programmes in place designed to support children from deprived backgrounds reach their full potential. Some of these include:

- The Extended Schools and Full Service programmes;

- Targeting Social Need Funding;

- Literacy and numeracy strategy Count Read Succeed;

- Getting Ready to Learn Programme;

- The Pathway Fund; and

- The Education Maintenance allowance.

The Department of Education also recently produced a research paper entitled ‘Tackling Educational Disadvantage – 10 Features of Effective Schools “Star” Case Studies’. The paper identifies 10 key features of local post-primary schools that have been successfully tackling educational disadvantage in Northern Ireland. The features include:

- Strong, committed and visible leadership;

- Committed teachers and staff;

- High expectations of and aspirations for all pupils;

- Effective pastoral care and positive behavioural management;

- Broad and balanced curriculum with a focus on literacy and numeracy;

- Skilled use of data to track pupil performance;

- Cross-phase links to support transition and to identify, apply and share best practice;

- Effective use of outside interventions;

- Good links with parents, communities and employers; and

- A well-informed and skilled Board of Governors committed to supporting the school.

The findings from the research broadly reflect findings in international literature on best practice actions and interventions to mitigate disadvantage and reduce educational underachievement.

The Equality Commission has commended the pro-active steps taken by a range of bodies, including government departments across all the sectors, to promote equality in education while at the same time acknowledging that significant challenges remain.

Supporting disadvantaged students through COVID-19

In September, the Education Minister, launched the ‘Engage programme’ which forms a significant part of efforts to address the impact of COVID-19 on pupils’ education, particularly for disadvantaged students. The programme, which had been given £11.2 million funding, will enable primary and post primary schools to provide additional teaching support for pupils, particularly those from disadvantaged backgrounds. Through the same funding package, the Department has helped schools with the purchase of online virtual learning resources for current P7 children to help with literacy and numeracy skills over the next year.

An inclusive approach to solving educational inequality

The six-member Panel set up to examine the links between educational underachievement and social disadvantage is being led by Professor Noel Purdy of Stranmmills College and includes leading educationalists and community representatives. Dr Purdy said of the Review:

The scope of the Review is broad, embracing early years provision (and earlier where appropriate), primary, post-primary, as well as family, parent and community involvement. I look forward to engaging with a very broad cross-section of our community to address what is a multi-faceted issue requiring engagement from schools, families, children and young people, and the community.

The Expert Panel is inviting written submissions from all interested parties who have experience of the issues associated with educational underachievement linked to socio-economic disadvantage through the supporting secretariat.

Education Minister Peter Weir said:

The Expert Panel on Educational Underachievement has the potential to significantly improve the outcomes for thousands of children and young people in Northern Ireland and I would encourage as many people as possible to have their say.

The establishment of the panel has been broadly welcomed as a positive step towards solving the long standing issue of educational underachievement in Northern Ireland. However, commentators have been quick to highlight that any report must outline ‘real and palpable actions’ as well as a ‘commitment’ by the Minister to effectively address the issues.

_______________________

[1] Burns, S., Leitch, R., Hughes, J. (2015) Education Inequalities in Northern Ireland Belfast: Queen’s University Belfast, Harland, K., McCready, S. (2012) Taking Boys Seriously – A Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Male School-Life Experiences in Northern Ireland Bangor: DE and OECD (2015) The ABC of Gender Equality in Education Paris: OECD Publishing