Transport links between Northern Ireland and the rest of the United Kingdom (UK) have entered the spotlight in recent months. The realities of the UK leaving the European Union mean that there has been greater focus on how both people and goods travel. Equally, in March 2021 the Union Connectivity Review (‘Connectivity Review’) released its interim report. Sir Peter Hendy CBE is undertaking this review on behalf of the UK Government. As was in the press, one area the Review will be investigating is ‘a fixed link between Northern Ireland and the British mainland’.

This blog post looks at how people currently travel between Northern Ireland and the rest of the UK, using the most recent data from the Whitehall Department for Transport and the Civil Aviation Authority. It looks at both sea and air travel, and the impacts of the pandemic on both. It also looks at the Connectivity Review’s interim report and its initial findings with regards to Northern Ireland.

Travel by air

According to the most recent data from the Civil Aviation Authority (CAA), in 2019, Northern Ireland’s three airports (George Best Belfast City Airport, Belfast International, and City of Derry) handled 6,575,945 domestic passengers between them. This total includes: (i) incoming passengers flying to NI (ii) outgoing passengers flying from NI and, (iii) those who were catching a connecting flight. Table 1 and Figure 1 show the five most popular UK destinations from each airport, along with the total number of passengers transported.

| International | City | Derry |

| Heathrow (668,575) |

Gatwick (581,909) |

Liverpool (58,533) |

| Manchester (275,852) |

Liverpool (492,312) |

Glasgow (14,363) |

| Birmingham (269,559) |

Manchester (470,260) |

Manchester (9,518) |

| London City (212,767) |

Edinburgh (330,759) |

Stanstead (7,180) |

| Edinburgh (151,512) |

Glasgow (293,804) |

– |

Table 1: The top five UK destinations from each Northern Ireland airport in 2019, with the number of passengers (source: Civil Aviation Authority (CAA); accessed 2021)

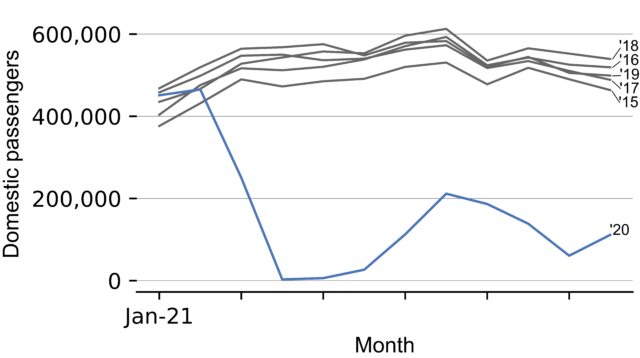

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a major impact on the passenger numbers for 2020. Figure 2 shows the total domestic passengers to Northern Ireland airports since 2014. The line for 2020 is highlighted in blue. The drop in March 2020 is very clear, and it can be seen that even in the summer, with minimal restrictions, passenger numbers did not return to anywhere near normal levels. The lowest recorded number was 2,878 passengers in April 2020. The vast majority of passengers that month (94.4%) flew between Belfast International and Heathrow. The remainder travelled on the only other operational routes: Derry-Southend and Derry-Stansted.

Travel by sea

Discounting the seasonal line to the Isle of Man, there are three current ferry routes between Northern Ireland and the rest of the UK. These are shown in Figure 3, with the passenger totals for 2019, collected by the UK Department for Transport, given in Table 2. It can be seen that the Belfast to Cairnryan crossing is by far the most popular route; transporting nearly double the number of passengers as the other routes combined.

| Route | 2019 passengers |

| Belfast – Cairnryan | 1,303,664 |

| Larne – Cairnryan | 466,756 |

| Belfast – Liverpool | 297,687 |

| Other | 13,435 |

Table 2: 2019 passenger numbers for ferry routes to and from Northern Ireland ports (source: Department for Transport (DfT) 2020)

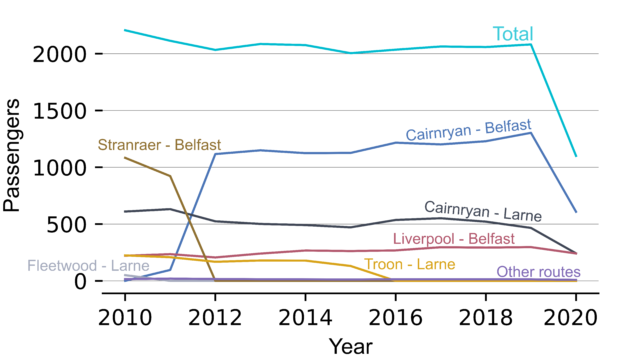

Figure 4 shows the trends in ferry passenger transport since 2010. The closure of Stranraer ferry port in 2011 is clearly visible, alongside the opening of the Cairnryan-Belfast line. A similar, if smaller, effect can be seen with the closure of Fleetwood in 2015. Between 2016 and 2020, although individual routes varied, the total has remained relatively flat. This potentially implies that there may not have been any major influence either way by the results of the referendum on leaving the European Union. Data is not yet available for 2021, and so it cannot be seen whether the end of the transition period has had an effect.

The effects of the pandemic are also clear, with total passenger traffic falling by more than half between 2019 and 2020. Notably, the Liverpool-Belfast line has been less affected than others; showing only an 18% fall on 2019’s numbers. The reason for this is not clear from the data available. One possibility is that the passengers on this service might be more predominantly freight and business travellers. Equally, it could be that border restrictions between England and Scotland made travellers who would otherwise go to Cairnryan choose Liverpool instead.

Freight

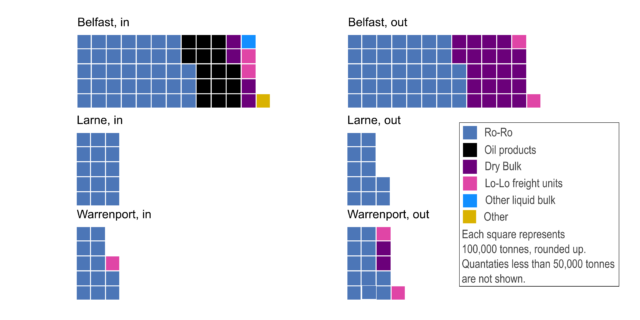

Figure 5 shows the composition of freight coming from and going to the rest of the UK through Northern Ireland’s ports in 2019. The freight falls into six categories:

- Ro-Ro (roll-on, roll off) mostly refers to ‘road goods trailers’, which can be thought of as a ‘standard’ lorry trailer. Data is not kept regarding the contents of these. The category also covers ‘import/export motor vehicles’, although they do not feature significant in the data;

- Oil products are petrol and diesel but not crude oil, which would be recorded under its own category;

- Dry bulk covers raw materials, transported unpackaged. This can include things like building foodstuffs, materials, metals, and wood pellets;

- Lo-lo (Lift-On, Lift-Off) refers to shipping containers. As with Ro-Ro, the data is not kept on the contents of Lo-Lo shipping containers;

- Other liquid bulk includes any unpackaged liquids which are not crude oil or an oil product. These can include animal and vegetable oils, milk, chemical fertilisers and industrial chemicals; and

- Other covers a number of categories. In the case of the Port of Belfast, most of the other freight is iron or steel products.

More information on how goods are categorised is available in a flow chart from the UK Department for Transport.

As each square represents 100,000 tonnes, this means that around 6.1 million tonnes of Ro-Ro freight passed each way through the port of Belfast. It can be seen that 1.5 million tonnes of oil products entered Northern Ireland through the rest of the UK. Around a quarter (470,000 tonnes) of the exported dry bulk through the port of Belfast is coal, with the rest being ‘other dry bulk’ (1,630,000 tonnes) or agricultural products (19,000 tonnes).

In 2019, Belfast City and International airports handled 13,900 tonnes of domestic freight total. The majority of this went through Belfast International, putting it second in the UK for the amount of domestic freight handled, below East Midlands International (38,000 tonnes) and above Edinburgh (9,500 tonnes). In addition, 7,000 tonnes of domestic mail passed through Belfast International airport in 2019.

Points raised by the Connectivity Review

According to its interim report, published in March 2021, the Connectivity Review is ‘an opportunity to assess current transport connectivity within and between the nations of the UK’ and aims to ‘make recommendations that will maximise economic potential and improve quality of life’. The motivation behind the Review is three-fold:

- While devolution has been ‘good for transport where its delivery has been devolved’, competing priorities and complex funding has led to a lack of attention to connectivity between the devolved nations;

- The UK Government’s ‘levelling up’ agenda, including the November 2020 review of the Green Book which guides options appraisal, has brought a focus on the way transport investment is prioritised. The Green Book review emphasises the need for a more strategic approach; and

- The departure of the UK from the European Union has meant leaving the Trans-European Transport Network, which implements travel connections between ‘nodes’ across the EU. The Connectivity Review notes that this creates an opportunity to create an equivalent UK Network, focused on the specific needs of the UK.

Regarding Northern Ireland, so far the Review has noted the need for:

- Faster and higher capacity connections from Belfast to north-west Northern Ireland, and to the Republic of Ireland;

- A higher capacity and faster connection on the A75 from the ferry port at Cairnryan to the M6 corridor; and

- Better air links between England and Northern Ireland, as well as adjusting air passenger rate to take account for the fact that rail is not a feasible alternative.

The review will also look into the possibility of a fixed link between Northern Ireland and the rest of the UK. This is being done with the assistance of two academics: Professor Douglas Oakervee, CBE; and, Professor Gordon Masterton, OBE.

Although the review is being undertaken at the behest of the UK Government, transport policy is a devolved matter. Responsibility for the road network within Northern Ireland lies with the Department for Infrastructure; while the roads between Cairnryan and the M6 are a matter for Transport Scotland. More information on transport infrastructure in Northern Ireland can be found in a December 2016 Research and Information Service research paper. However, it should be noted that both aviation and shipping are matters reserved to the UK Government, so any recommendations the review might make in those areas would be the responsibility of the UK Government. This would likely also apply to any direct link, whether that be by bridge or tunnel.

The final report from the review is expected in summer 2021. Key things to potentially look out for in that report include:

- The response from the UK government, including whether any additional funding is made available for infrastructure projects within Northern Ireland: it is not yet clear whether the UK Government plans to use the UK Share Prosperity Fund, which aims to replace certain other EU funding streams, or whether some other funding mechanism would be used. The interim report notes that support for the scheme by the devolved governments was caveated by a need for ‘a clear and strong commitment to additional funding’. In March 2021, the UK Government committed £20 million towards exploring the development of projects identified by the interim report;

- What infrastructure projects are recommended within Northern Ireland, and how these might interact with other existing and planned projects: depending on how the proposals are implemented, they might impact the cost-benefit analysis of these projects. Examples of projects which might be interact in this way include Better Connecting Belfast & Dublin, which aims to decrease rail journey times between the two cities, and upgrades to the A6, which is part of the Northwest Travel Corridor;

- Whether or not the report recommends a reduction in Air Passenger Duty, which could lead to cheaper flights;

- The outcomes (if any) of the review into a fixed link between Northern Ireland and the rest of the UK, including the secondary effects this might have on areas such as traffic, the local economy, the environment, and port; and

- What recommendations are made in terms of freight capacity to and from Northern Ireland. These are mentioned in the interim report in relation to Brexit. While the Ireland/NI Protocol is not listed as an interdependency, its effects will likely inform the final report.