Reservoir safety is changing in order to better protect people in Northern Ireland. This article gives an overview of a recent Research and Information Service paper about the Reservoirs Act (Northern Ireland) 2015. It explains why regulation was introduced, what this involves, when the new regime will come into force, and how reservoir management might change as a result in the coming years.

What is a reservoir?

A reservoir is a structure built to store surface water. Water may be used for farming, industry, and household consumption. Alternatively, it can maintain navigable waterways, generate hydroelectricity, and provide recreational opportunities.

There are two main types of reservoir structure in Northern Ireland (NI):

Embankment dam

These dams are constructed using earth or rock, with an impermeable clay core, and shaped like a long hill. They include most small reservoirs in NI, such as Knockbracken (now ‘Let’s Go Hydro’ waterpark) and some large ones, such as Silent Valley.

Gravity dam

These are constructed using concrete or masonry. They have triangular cross-sections and are held down by gravity. This type includes a few of the larger reservoirs in NI, such as Ben Crom.

How many reservoirs are there in Northern Ireland?

There are 179 known controlled reservoirs (those with over 10,000 m3 capacity) in NI. There are also an unknown number of smaller impoundments, including ornamental ponds, fishing lakes and mill dams. Many of these were built in the nineteenth century.

Controlled reservoirs

In the Reservoirs Act (Northern Ireland) 2015, the threshold for a ‘controlled reservoir’ is 10,000 m3 (cubic metres). This is equivalent to the volume of four Olympic-sized swimming pools.

As an example, the ‘Let’s Go Hydro’ waterpark has an area of around 70,000 m2. Assuming an average depth of 1.43 m, it would have a 10,000 m3 volume.

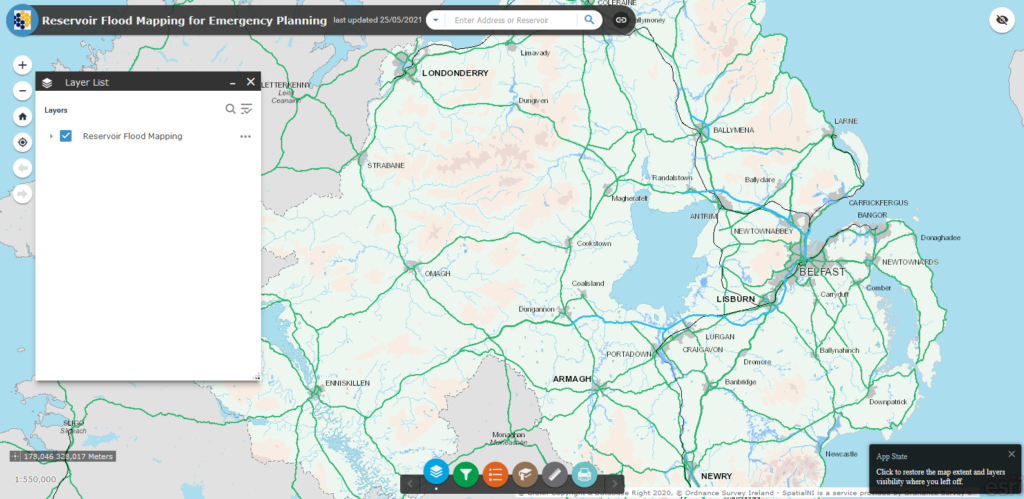

A map of NI’s controlled reservoirs and their maximum potential flood extents has been compiled by the Department for Infrastructure (DfI):

Why is reservoir safety important?

Reservoirs can hold huge volumes of water. A sudden, uncontrolled release of water would be very dangerous. Although dam failures are rare, there are occasional disasters. The 1864 Dale Dyke disaster killed 244 people in the Sheffield area in England. In February 2021, the (under-construction) Rishi Ganga dam in India’s Uttarakhand state failed, killing at least 72 people.

Reservoir safety in England, Wales, Scotland and Republic of Ireland

Until 1930 reservoir owners in Ireland and Great Britain had only a common law duty to ensure that uncontrolled releases did not harm people or damage property. This remains the case in the Republic of Ireland.

Great Britain’s first reservoir safety legislation was the Reservoirs (Safety Provisions) Act 1930. This was repealed by the Reservoirs Act 1975. The Act applies to ‘large raised reservoirs’ (those with over 25,000 m3 capacity). In 2016, Wales lowered the registration threshold to 10,000 m3. Similar changes could follow in England and Scotland.

The Act establishes some key roles relating to reservoir safety:

- Undertaker: The owner, operator, or nominated representative. Responsible for day-to-day inspections and, for high-risk reservoirs, commissioning reservoir engineers;

- Supervising Engineer: A qualified member of the Supervising Engineers Panel. Commissioned by the Undertaker to supervise the reservoir at all times and provide an annual report;

- Inspecting Engineer: A qualified member of the All Reservoirs Engineers Panel. Commissioned to inspect the reservoir at least once every ten years and provide a report to the Undertaker.

Key features of the Reservoirs Act (Northern Ireland) 2015

Fortunately, no lives have been lost due to dam failure in NI. However, several dam failures have caused property damage. In 1998 the collapse of a weir at Tildarg Dam, County Antrim was blamed for the flooding of houses in the Doagh area. Concerns that some ageing dams were not being rigorously inspected and maintained led to calls to regulate reservoir safety in NI. The result was the Reservoirs Act (Northern Ireland) 2015. The Act is similar to Great Britain’s Reservoirs Act 1975. The key features of the NI Act are:

- Registration: ‘Reservoir managers’ must register ‘controlled reservoirs’

- Registration threshold: Reservoirs over 10,000 m3

- Designation: Reservoirs designated as ‘high’, ‘medium’ or ‘low’ consequence

- Reservoir engineers: Must be commissioned to supervise and inspect reservoirs

- Compliance: Reservoir managers must comply with reservoir engineers’ recommendations

This table summarises the key features of reservoir safety regulations in England, Wales, Scotland, Northern Ireland and Republic of Ireland:

| England | Wales | Scotland | Northern Ireland | Republic of Ireland | |

| Main legislation | Reservoirs Act 1975. | Reservoirs (Scotland) Act 2011. | Reservoirs Act (Northern Ireland) 2015 | Common law only | |

| Regulatory authority | Environment Agency | Natural Resources Wales | Scottish Environment Protection Agency | Department for Infrastructure (DfI) | N/A |

| Registration threshold | 25,000 m3 | 10,000 m3 | 25,000 m3 | 10,000 m3 | N/A |

| Risk designations | High risk only | High risk only | High, medium and low risk | High, medium and low consequence | N/A |

Table 1: A comparison of key features of reservoir safety regulations in England, Wales, Scotland, Northern Ireland and Republic of Ireland

How well is the new safety regime working?

The new safety regime is not yet in place. The Act is primary legislation, which sets out the aims and general form of the regulations. Before it comes into force, the responsible Department must develop technical details, such as the designation criteria, and put forward secondary legislation. However, administrative error in the 2016 departmental reorganisation left the Act in a legislative limbo. The NI Executive’s three-year hiatus between 2017 and 2020 caused further delays. The issue was resolved on 1 June 2021, when the Act became the responsibility of DfI.

When will the Act be implemented?

A few parts of the Act have already been commenced. DfI aims to introduce orders and regulations to implement the key elements of the Act during the current mandate (by April 2022). When the Act has been fully commenced, the regulatory regime will be implemented.

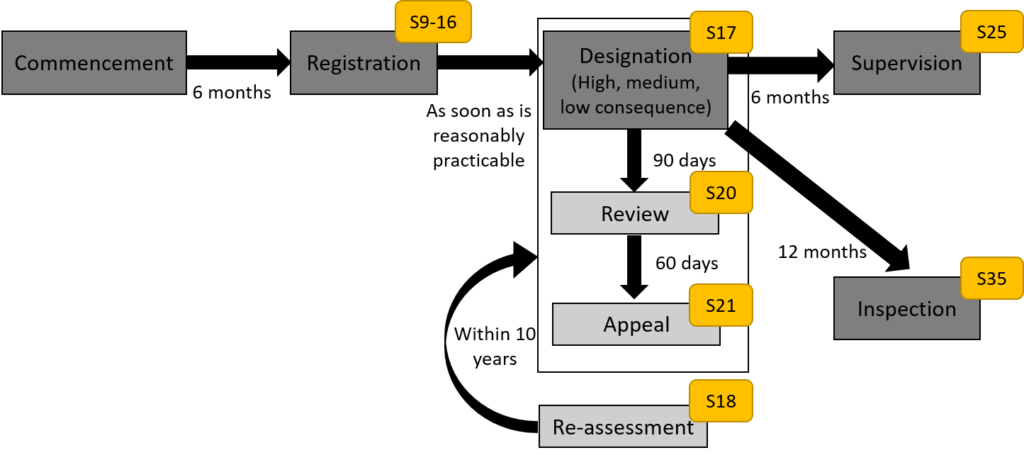

This diagram shows the sequence and timescales for the implementation of the Act’s reservoir safety regime:

What is being done to ensure reservoir safety in the meantime?

Without the Act, DfI cannot enforce the new reservoir safety regime. Nonetheless, it has been working to improve reservoir safety. A national audit has identified 28 controlled reservoirs that were unknown before 2015, bringing the total to 179. In 2016, DfI identified 45 reservoirs in poor condition, and reminded managers of their common law duties to keep them safe. In some cases, DfI directly employed reservoir engineers to carry out inspections. By the end of 2020, there were up to nine reservoirs deemed to require urgent interventions, some of which have been completed.

New costs due to the Act

The implementation of the Act will create new costs for reservoir managers if they were not already complying with the spirit of the 1975 Act:

Registration, supervision and inspection costs

DfI has the power to charge for reservoir registration and administration. In Scotland and Wales, one-time registration costs around £500, and annual administration fees cost a few hundred pounds. Meanwhile, employing a Supervising Engineer can cost a few thousand pounds per year. Furthermore, an Inspecting Engineer’s report must be completed at least once every ten years and can cost around £10,000.

Remedial works costs

Some reservoir managers may have not carried out any maintenance or repairs for many years. Newly mandatory remedial works in the interests of safety may be expensive. Costs may range from around £10,000 for minor works, to over £1 million for substantial works on large dams. DfI may decide to introduce time-limited capital grants to help reservoir managers meet these new costs.

Recent themes in reservoir management

In addition to the increased costs of new safety regulations, reservoir management is influenced by economics, stakeholder interests, and environmental requirements. Several reservoirs have been subject to news headlines and discussions in the Assembly during recent years. Recurring themes include the following:

Discontinuance (partial decommissioning)

This is the alteration of a reservoir to make it incapable of holding 10,000 m3 of water. This may involve lowering a dam spillway, or breaching an embankment. Such works must be supervised and certified by a Construction Engineer.

Abandonment (full decommissioning)

This is the alteration of a reservoir to make it incapable of filling with water above the natural ground level. This may include removing an embankment. Such works must be supervised and certified by a Construction Engineer.

Lowering

Reservoir water levels may be lowered by releasing water in a controlled manner. Although this may temporarily reduce risk, levels can recover unless the reservoir has been decommissioned. Examples of this include Boghill Dam and Hydepark Dam in County Antrim which were lowered over safety concerns. Local stakeholders may have concerns about impacts on amenity, wildlife, and recreation.

Sales

Reservoirs may be sold to a new owner, who would then assume responsibility for safety. For example, NI Water sold the disused Knockbracken reservoir in County Down, which has been redeveloped as ‘Let’s Go Hydro’ waterpark.

Issues caused by delays in bringing the Act into force

Development delays

Building developments downstream of reservoirs should take place only if the reservoir is in good condition. After 2015, planning authorities required ‘condition assurance’ in order to grant planning permission. Since the new safety regime was not in force, this wasn’t always forthcoming. In response, DfI created an interim scheme whereby a reservoir manager can voluntarily agree to comply with ‘key provisions’ of the Act. DfI can then confer ‘Responsible Reservoir Manager Status’ on the reservoir and give a planning authority ‘condition assurance’, to unlock development.

Summary and outlook

The Reservoirs Act (Northern Ireland) 2015 was introduced to improve reservoir safety. Yet due to administrative and political problems, the Act has not been brought into force. Despite this, DfI has persuaded some reservoir managers to voluntarily make safety improvements.

DfI is now responsible for bringing the Act into force. Key policies yet to be announced include the reservoir designation criteria, and availability of capital grants for remedial works. Assuming the Act is brought into force by April 2022, a fully functioning reservoir safety regime ought to be in place by 2024. As a result, we may expect more reservoir engineering works, decommissioning and sales over the next few years. Ultimately, this should better protect our communities from the rare, but potentially disastrous, hazard of dam failure.