The UK Government has a vision where almost all cars and vans on UK roads will be electric by 2050. Encouragingly, the market for electric cars is growing year-on-year, though realistically they continue to make up a tiny share of cars on the roads. This blog article examines some of the key trends and policies driving ecars into the mainstream.

The electric car market in Europe

Around Europe, more people are buying Ultra Low Emission Vehicles (ULEV) than ever before. In fact Europe overtook China as the world’s largest ULEV market for the first time in 2020, with one in every ten cars sold a ULEV. By the end of 2020, 1% of passenger cars driving on European roads were electric.

| What is a ULEV?

By the UK Government’s definition, ULEVs are vehicles that emit less than 75g of carbon dioxide (CO2) from the tailpipe for every kilometre travelled. In practice, the term typically refers to battery electric (zero emission) and plug-in hybrid electric (reduced emission) vehicles. In this article, ULEV refers to battery electric and plug-in hybrid vehicles. |

The majority of ULEV passenger cars on European roads are concentrated in Germany, Norway, the United Kingdom, France, and the Netherlands with a combined share of 70% of Europe’s ULEV passenger car fleet. Norway has the largest ULEV fleet share, with 16% of all cars ULEV.

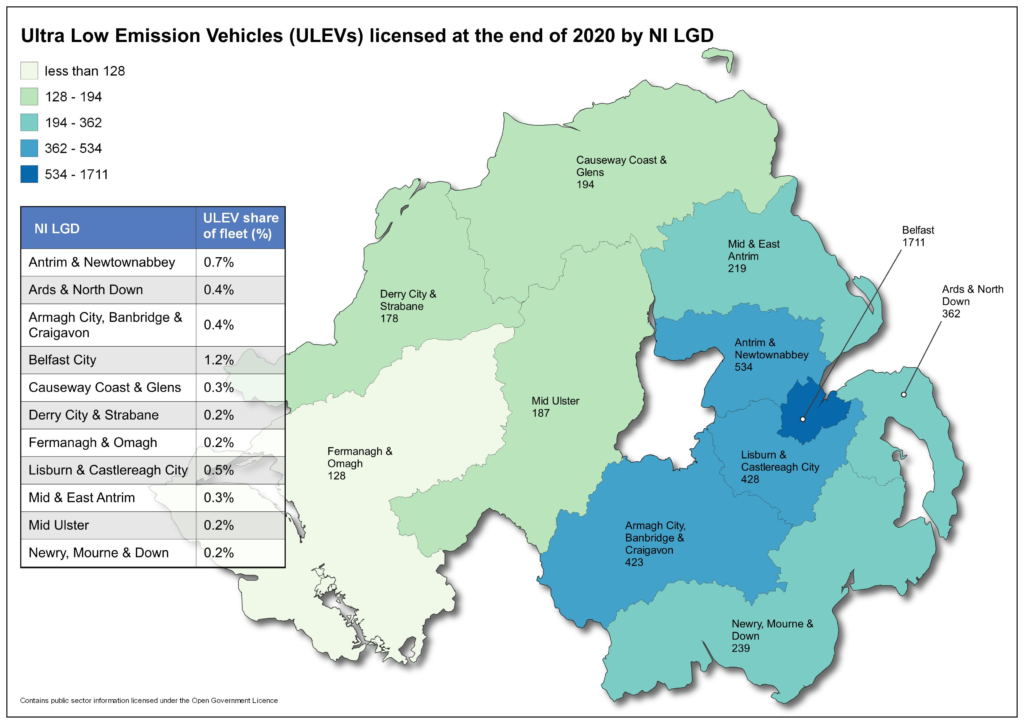

In terms of the number of vehicles, the UK has the third largest ULEV fleet in Europe. However, in terms of fleet share, ULEV make up just over 1% of cars on the road. There are regional differences to take into account; at the end of 2020 NI had the smallest ULEV fleet of the UK’s main devolved regions (0.49%), slightly smaller than Wales (0.52%) and less than half the size of Scotland (1.04%) and England (1.43%). Within Northern Ireland, the largest number of ULEV are concentrated in the east and Belfast has the largest fleet share of ULEV.

The UK’s current ULEV fleet share falls well short of the 9% target set by the Committee on Climate Change in 2015. However, ULEV do appear to be achieving significant market penetration in recent years. In 2020, ULEV took an almost 11% market share in the UK, of which 6.4% were zero emission battery electric vehicles (BEV) and 4.3% were plug-in hybrids (PHEV). Among the three devolved regions, Scotland has the fastest growing market; in 2020 ULEVs had a 8.6% market share in Scotland, compared with 6% in Wales and 5.4% in NI. Norway, Iceland, and the Netherlands are leading the way in Europe, recording market shares for new ULEV of some 75%, 51% and 25% respectively in 2020.

Figure 2: Market share of new BEV/PHEV versus other fuel types, selected countries 2020 (chart: Country vs % Market share | made by Astennett | plotly; data source: European Alternative Fuel Observatory)

Phase out targets

The UK’s Road to Zero Strategy envisions that by 2050 almost every car and van on UK roads will be zero emission. The key policy lever in driving this ambition is the announcement that the sale of new petrol and diesel cars and vans will be phased out by 2030, and all new cars and vans will be fully zero emission at the tailpipe from 2035. Phase out targets send a message to consumers that times are changing and perhaps more importantly to the car manufacturing industry that it must change. What phase out targets do not do is address the many perceived and often real barriers to EV uptake such as poor infrastructure provision, the consumer experience of using that infrastructure, and vehicle price and supply.

Vehicle supply

National phase-out goals have prompted many of the top car manufacturers to announce their own plans to gradually phase out production of internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles. Volkswagen Group, PSA Group, Renault Group, Hyundai Motor Group, BMW Group, Daimler, Ford, Fiat Chrysler Automobiles Group, Toyota Group, and Volvo Car Group have announced plans to increase their production of ULEV while phasing out ICE production, over the next 10 years.

Already, it could be argued that the recent increases in ULEV sales have as much to do with supply-side factors as any government intervention. The increase in registrations strongly correlates with the introduction of new models, improved range and more affordable options. For example, at the end of 2018, the BMW i3 and the Renault Zoe were updated with increased battery capacity, Tesla introduced the Model 3, the company’s most affordable car and various manufacturers introduced battery-electric SUV models, like the Hyundai Kona and Audi e-tron. The Tesla Model 3 has established itself as the most popular BEV in the UK outselling its closest competitors by 2:1.

Figure 3: Electric car models available globally and average range, 2015-2020 (chart by A Stennett; data source: IEA)

Affordability

Affordability and vehicle prices are often cited in the top two or three reasons for not owning an electric car in the UK. Indeed, respondents to the NI Assembly Infrastructure Committee’s survey on ecars identified it as the second biggest barrier to ULEV uptake in NI.

In the UK today, a typical BEV car is around 35% more expensive to purchase than a comparable petrol or diesel car. Looking at different models, it is noticeable that the price disparity between ULEV and ICE comparators is more pronounced at the lower end of the market. For example:

- The Renault Zoe BEV starts at £27,595 whereas a Clio starts at £17,400 (41% more expensive);

- The Volkswagen ID.3 starts from £30,935 whereas Golf TSI starts at £23,625 (23% more expensive);

- The BMW i3 starting at £33,805 compared to £32,595 for a BMW 318i (3.5% more expensive).

To offset the higher purchase price, the UK Government offers the Plug-in Car Grant (PiCG). Since March 2021, the PiCG has been capped at £2,500, for fully electric cars (BEV) priced under £35,000. The BEV models above are eligible, whereas the UK’s most popular BEV, the Tesla Model 3, is not as it costs around £40,000.

An entry level car of around £28,000 is likely to be well beyond many households in the GB and Northern Ireland. The fact is that the majority of people do not purchase new cars and perhaps never will. Used car sales generally account for around three quarters of the total annual car sales market in the UK.

The UK Government does not provide any incentives for the purchase of used EV but the House of Commons Transport Select Committee has recently called for this policy to be reviewed pointing out that ‘…a healthy used electric vehicle market is critical to ensuring that electric vehicles are not the sole preserve of people who can afford new models’. The Transport Committee cited the example of grants for used cars that have recently been introduced in the Netherlands, France and Germany, already three of the top EV markets in Europe. It also cited the used electric vehicle loan in Scotland which provides £20,000, to be repaid over 5 years, to support the purchase of used EV.

The cost of ULEVs is falling, with industry analysts suggesting that upfront price parity with petrol and diesel vehicles could occur between 2025-27. They already offer substantial operating cost savings compared to petrol and diesel vehicles with cheaper (sometimes free) fuel and lower maintenance costs than conventional vehicles, that can save the owner up to £170 per year.

Infrastructure

There are a number of research reports that point to a lack of public charging points as a leading, if not the main, barrier to buying a ULEV. For example:

- In a poll of 17,628 drivers, taken on behalf of the AA, the top reason for not wanting an EV, identified by 69% of respondents, is a lack of public charging points.

- In a survey of 34,119 non EV users (taken on behalf of the All Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) for fair fuels for UK motorists and hauliers), 77% said that a lack of ‘charging point availability on route’, was a main reason for their ‘reluctance to buy electric’.

- Over 90% of respondents to the NI Assembly Infrastructure Committee’s survey identified the lack of charging infrastructure as the main disadvantage of EVs.

- Internationally, studies have pointed to access to charging, along with pricing incentives, to be the key factors in EV uptake.

Is home charging the answer?

The UK Government maintains that the vast majority of drivers will choose to charge at home, noting that EVs offer consumers a more convenient and cost-effective way to refuel – this is a view shared by the Department for Infrastructure.

It is hard to argue with this logic, charging at home while you are sleeping, at a lower cost than you would face at the pumps, sounds very attractive. For example, charging experts Pod Point state that a typical electric car with a 60kWh battery and 200-mile range costs about £8.40 for a full charge at home. This will have certainly been attractive to those queuing to fill their petrol and diesel vehicles amid the recent ‘fuel crisis’ in GB. Indeed, The Guardian reported that this event has triggered a massive spike in EV enquiries at many car dealerships.

Almost 90% of respondents to the Infrastructure Committee’s survey identified the ‘ability to charge at home’ as one of the most important factors in deciding to purchase a ULEV. Unsurprisingly most (89%) of the EV owners who responded to the survey had facilities to charge at home, but this isn’t to say they only charge at home. The survey found that:

- 72% charge at home at least a few days per week;

- 23% avail of work charging stations at least a few days per week;

- 35% use public infrastructure at least a few days per week;

- Over 75% of EV owners make use of public charging infrastructure at least a few days per month.

Whether or not most charging is done at home, a functional and comprehensive public charging network is critical, to enable top ups on the go and overcome range anxiety, which is a key barrier to uptake. The Committee on Climate Change (CCC) has identified the lack of an overarching strategy and targets for sufficient charging infrastructure, particularly on-street chargers as a key barrier to the UK Government realising its decarbonisation targets. Provision of public chargers is patchy across the UK and while some UK local authorities have bid for UK Government funding for charging devices, others have not, with the CCC pointing out over 167 Local Authorities have 20 or fewer charging points.

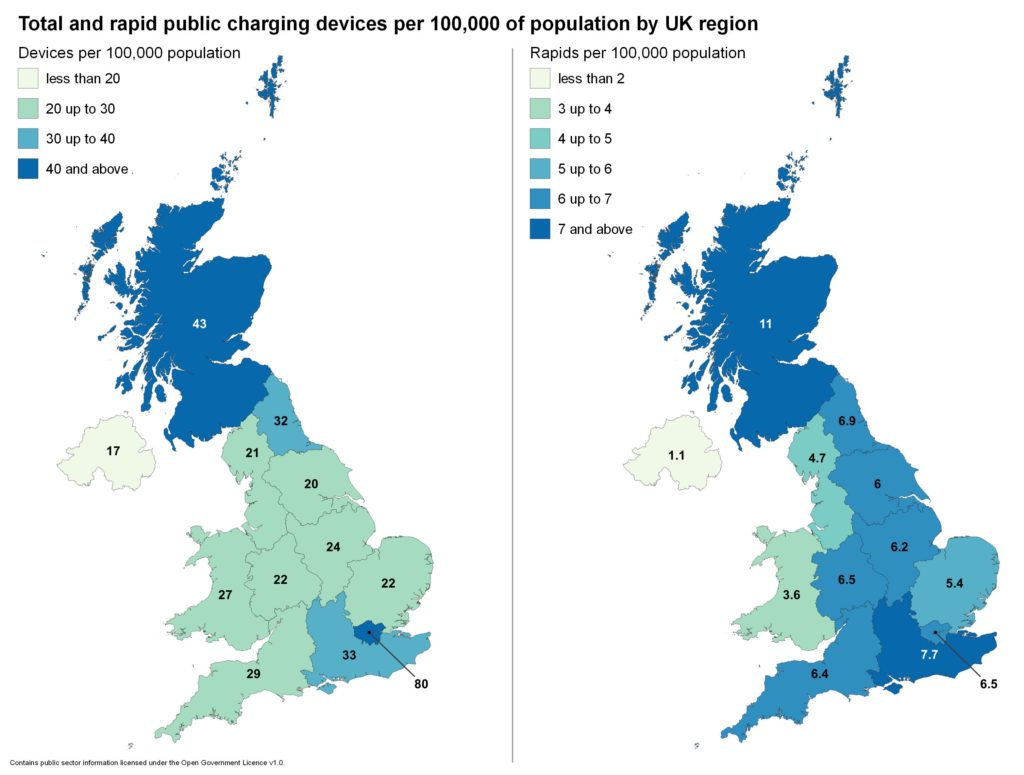

As of January 2021, NI had 320 public charging points, the lowest number of both standard (300) and rapid (20) charging points of any UK region. The map below shows there are 17 standard devices per 100,000 of the population and 1.1 rapid chargers per 100,000. The ratio of charging points per 100,000 is also the lowest of the UK regions.

The Electric Vehicle Association (EVA), a not-for-profit community interest company that represents the interests of electric vehicle users in Northern Ireland, stated that: ‘…the single overriding issue that faces EV drivers here [in NI] is the size and condition of the public-charging network’. The EVA’s own research found that in February 2021 ‘more than a quarter of AC chargers and around half of all DC chargers here are out of order’. The EVA noted that ‘…seeing blocked and broken chargers is a disincentive to anyone who is considering changing to an EV, but it is much worse if you already drive one’.

The NI Assembly Infrastructure Committee’s survey on ecars found that over 90% of current EV owners were dissatisfied with the availability and maintenance of public charging stations. The survey found that the network in its current state is actually encouraging some current ULEV drivers to revert back to ICE vehicles. The EVA and Committee’s research of EV drivers in NI both found evidence that the condition of the charging infrastructure was the main reason many EV drivers were reverting back to ICE vehicles.

The lack of chargers and poor reliability mean that drivers planning journeys beyond the range of their vehicle cannot be confident that the device they plan to charge at will be operational or indeed whether it will be there at all. There are numerous examples of devices listed on ZapMap that are either broken or have been completely removed.

Problems with the public network will have a particular impact on the ability of those who live in homes without an off-street parking space to transition to an electric car. Whilst it is difficult to pinpoint an exact figure, given 28% of the properties in NI are terraced houses and 7% are apartments, it is reasonable to estimate that installing a private charger may not be possible for around one third (270,000) of NI homes, meaning they will be almost entirely reliant on the public charging network.

It is clear that the transition to electric cars becoming mainstream has started – but it is equally clear there is a long way to go. A combination of UK Government incentives and industrial innovation is beginning to stimulate sales, albeit from an extremely low base level. Although the price of new vehicles is reducing, affordability remains a key barrier. Even if price parity is achieved by 2025-27 most people will continue to be priced out of the market until the used car market adjusts. Charging infrastructure remains a critical factor moving forward; research shows both potential and current ULEV drivers view an extensive, well maintained network, not as a luxury, but as a basic prerequisite for the acceptance of BEV as a mainstream alternative.