On 9 May 2019 the Permanent Secretary for the Department of Finance (DoF) announced a fresh appraisal of the fundamental features of the Northern Ireland (NI) rating system. This article provides some context for the Review. It addresses: how NI is funded currently; the relationship between funding by fiscal transfers to NI and rating; and key considerations arising from those funding arrangements, which could inform future rating in NI.

How NI public expenditure is funded

A majority of the spending allocated by the NI Executive, when it is fully functioning, (i.e. the NI Budget) comes from the ‘Block Grant’. Presently, as the Executive is not functioning, this allocation is determined by the Secretary of State for NI, in conjunction with the permanent secretaries of NI departments.

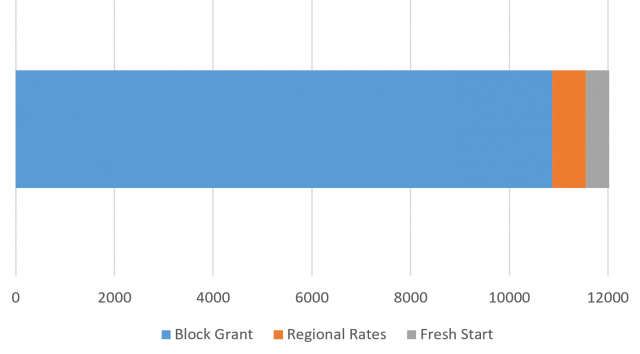

Figure 1 shows the breakdown between the Block Grant and other funding sources in the Executive’s last Budget, 2016-17.

Clearly, the Block Grant (in blue) is hugely significant to NI’s public finances. The funding shown in grey (£479.8 million, about 4% of the total) was specially agreed between the NI Executive, and the British and Irish Governments in the 2015 Fresh Start Agreement. The remaining 5.6% (orange) was raised through the Regional Rates under the NI rating system for domestic and non-domestic properties.

Both domestic and non-domestic ratepayers’ bills are comprised of two elements: the Regional Rate and the District Rate. The former funds centrally provided services, such as schools and hospitals; the latter funds local services such as waste management and leisure centres. (For a fuller explanation of the rating system in NI, refer to a previous blog article, What are rates and why do we pay them?)

Regional Rates raise only a small proportion of overall funding, but are particularly interesting because they are devolved to the Executive. When budgeting, the Executive (or the Secretary of State for NI in the absence of a power-sharing government since Budget 2016-17) decides how much it wishes to raise from the Regional Rates, and then sets the level accordingly. As such, they serve as a means to supplement (i.e. ‘top-up’) the Block Grant that is received from the United Kingdom (UK) Exchequer, as determined by UK Government Spending Reviews (SR). For a fuller explanation see the article Financing the Executive’s Budget in a previous RaISe publication, Consider This.

Limits of NI fiscal devolution

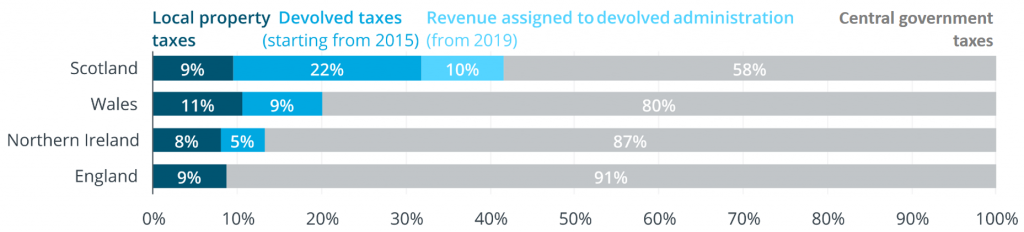

As shown in Figure 1, the proportion of the NI Budget that comes from the Block Grant is high and is higher than in the other UK devolved administrations, because both Scotland and Wales have more significant tax powers.

This was highlighted by a recent Institute for Government publication Devolution at 20. This illustrated how the proportion of devolved taxation in NI (5%) is lower than in Wales (9%), and considerably lower than in Scotland (22%). In other words, the amount of public expenditure that is funded by taxes which are set locally is higher in Scotland and Wales. So local politicians in those jurisdictions have more control over the total budget that is available for their respective devolved governments to spend.

However, the NI figure is based on devolved corporation tax and although legislation for its devolution is in place, it has not yet commenced. This means that, at present, the proportion of locally determined revenue in NI is actually lower than the 5% shown.

Figure 2 also highlights that 8% of NI expenditure is funded by local property taxation, which in NI is through the rating system, the focus of this blog article. Note that, in addition to the Regional Rates discussed above, this 8% also includes the District Rates, raised and spent by local councils.

To summarise, NI Executive revenue raising is limited and the fiscal transfer to NI via the Block Grant is more important. To further understand the parameters of future debate about rating in NI, we must consider what the UK Chancellor’s next Spending Review (SR) may deliver for NI. As shown above, the Chancellor’s decisions will clearly have significant impact on the resources available for allocation to NI public services. If the Chancellor continues along the path of austerity, the pressure on the rating system to raise money to supplement the Block Grant seems likely to increase over the short-to-medium term.

Future spending envelope

In March 2019, the Chancellor said the next SR would begin this summer concluding alongside the 2019 Autumn Budget. It would establish NI’s ‘spending envelope’ for – probably – the next three years, but acknowledged Brexit uncertainty continues. In April, the Chancellor told Parliament it would be “unwise” to make a three-year settlement before a Brexit deal is agreed.

Leaving aside the uncertainty surrounding the precise timetable for the SR, these UK-level fiscal events are important for funding public services in NI, because much of NI public expenditure is financed through fiscal transfers from revenue raised elsewhere (see RaISe blog article: How much of what we spend on public services in Northern Ireland is paid for by locally raised tax revenue?). Also, the SR follows years of austerity; many of NI’s public services are already under pressure.

Services under financial pressure

Some examples of NI services under pressure are:

- Shortages in school budgets are well documented: current provision was recently described by the Association of School and College Leaders as ‘financially and educationally unviable’;

- NI’s Health and Social Care system faces multiple financial pressures: in 2016, the Bengoa Report stated:

If costs rise as predicted, with a 6% budget increase required annually simply to stand still, then we can expect the budgetary requirement to double to more than £9 billion by 2026/27 to maintain the current system.

- The arts are under pressure, too, with the chief executive at the MAC recently stating that the NI arts sector ‘has sustained a 40% real-terms cut, including inflation, between 2012 and 2017‘.

2019 Rating Review

Against the above backdrop, the DoF upcoming Review will ‘assess and respond to the significant changes that have taken place in relation to Northern Ireland high streets and town centres’.

It may change the NI rating system, but thoughts of reforming rating are not entirely new. In December 2016, just before the collapse of power-sharing, DoF published a Rates Rethink. Amongst other things, this document suggested that,

…a demand-led stimulus through the rating system could prove effective in order to increase ‘city/town centre’ living.

Other potential measures included:

- A Rates Investment Scheme for smaller retail and hospitality business

- Piloting Business Empowerment Zones in two areas (Lower Newtownards and Lower Falls Roads)

- Increasing rates on empty commercial properties

- Charity shops to make a contribution

- Charging the highest value homes more

- Removing the early payment discount

- Reducing landlord allowances

- Student halls of residence to start paying rates

- A three year rates holiday for first residents of new energy efficient homes

Some organisations published their responses to the Rates Rethink, raising a range of issues, which appear relevant to this 2019 Review. The Executive collapsed before DoF published a consultation analysis and in the absence of that publication, the following highlights a selection of issues raised by stakeholders in their submissions:

- The Institute for Revenues, Rating and Valuation noted a possible Brexit-related risk: ‘Any measure that enables businesses to survive and prosper in the current period of economic uncertainty should be applauded. As stated above, small businesses have a major role in regenerating towns and cities particularly with the challenge of Brexit and the potential for hostile cross-border retail activity’;

- The Charity Retail Association, however, were concerned about removal of or change to the existing relief for charity shops: ‘Even slightly tampering with the current system would jeopardise this great work and is therefore not worth the risk to the Northern Ireland Executive’.

- Enterprise NI stated that targeting rates relief on retail and hospitality: ‘would be sending out a message that microenterprises and small businesses in other sectors – those who represent the vast majority of the private sector business base – are simply not valued’.

The 2019 Review is aimed at enabling the DoF to provide more current advice to a future Executive. At present, however, it remains to be seen how far the Review will go. For example, will it address the reliefs and ‘super parity’ measures discussed below?

Rate Reliefs

Some properties are exempt from rates altogether (such as churches and agricultural buildings). In other cases, the occupiers get reliefs from their liability based on their circumstances. Existing non-domestic reliefs include Small Business Rate Relief, Empty Property Relief. Charity shops and vacant properties are exempt, and industrial premises are ‘derated’ to 30% of their assessed liability.

Domestic reliefs include an early payment discount, landlord allowance, a cap on the maximum rateable capital value of properties, and other discounts for lone pensioners, disabled persons and so on.

These reliefs have developed over time, and are based on policy choices made by devolved government in NI. They now may or may not represent the best policy mix for current circumstances in NI. It will be interesting to see if and how the Review addresses these reliefs.

Super-parity

Another potential issue that the Review could address is the use of ‘super-parity’ to increase NI public spending power. ‘Super-parity’ was described by the Ulster University Economic Policy Centre as:

…the extent to which even when compared to GB regions such as parts of Wales or the North of England which have very similar socio-economic conditions to NI (e.g. level of GDP per head or unemployment rate), the rate of regional taxation in NI is considerably lower (notably, lower domestic Rates coupled to the absence of domestic Water Charges). Free prescriptions, free public transport for the 60+, lower Tuition Fees have contributed to such super-parity.

In 2014, during an Assembly debate on Executive Budget 2015-16, the then Finance Minister stated:

…Members will be aware of the calls by some to raise more revenue by stopping so-called super-parity measures. In my view, those who argue that the answer to our budgetary problems is simply to introduce water charges or to hike rates bills are wrong and misguided.

Taking stock?

The above and many other issues may well be considered during this 2019 Rating Review. The Review affords an important opportunity to take stock of how best could NI’s limited fiscal powers be deployed most effectively, striking appropriate balances between stakeholders’ competing interests.

Further informing those deliberations could be evidence compiled during the on-going Treasury Committee’s inquiry in the House of Commons into how UK Government policy impacts business. Whilst rating system differences exist, perhaps some of the evidence heard during that inquiry would be of relevance to the Review in NI.