Governments around the world have undertaken very significant, and hugely costly, actions attempting to prop up businesses and employment through the course of the pandemic. The UK Government is no exception, with a wide variety of schemes to support businesses and protect employees’ jobs and incomes.

The Executive, through the provision of rates reliefs and other measures, has supplemented these in Northern Ireland (NI). This blog article considers how COVID-19’s accompanying economic contagion may infect NI’s public finances. To explain how this might happen, it first addresses devolved public financial arrangements, before reviewing available evidence on what the future might hold.

It seems unavoidable that there will be impacts on the UK’s devolved administrations’ future budgets, and the Scottish Parliament’s Finance and Constitution Committee last month issued a call for evidence on the impact of COVID-19 on the public finances and the Fiscal Framework in Scotland.

The NI Public Finance Framework

The NI Public Finance Framework (PFF) comprises the law, procedural rules, non-statutory guidance and policy documents, at both UK and NI levels, which govern how public finance is managed. (See RaISe paper Assembly Committees: Coordinated Budget Scrutiny for more information, in particular some changes due to the COVID-19 pandemic.)

Circumstances have resulted in an extremely compressed timetable for the Executive to formulate its Budget 2020-21, and for the Assembly to scrutinise that Budget. Also, the UK Chancellor’s planned Spending Review (SR) has been delayed, which will have knock-on consequences for how devolved public finances are managed in the short term.

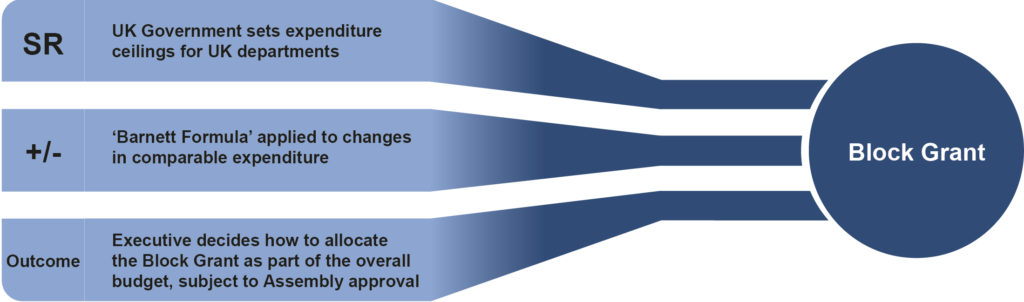

A key element of the PFF is the UK Treasury’s Statement of Funding Policy, which sets out the funding arrangements for NI, Scotland and Wales. For NI, the Block Grant from the UK, via the Barnett Formula is hugely significant. (For more on the Block Grant and the UK-to-NI fiscal transfer, see RaISe blog article, How much of what we spend on public services in Northern Ireland is paid for by locally raised tax revenue?) Figure 1 shows how the Block Grant is determined.

The Block Grant is particularly important to NI because of the Executive’s limited devolved fiscal powers, when compared to both Scotland and Wales.

NI’s limited fiscal powers

Under their respective fiscal framework agreements, the devolved governments in Scotland and Wales have greater fiscal powers than the NI Executive (shown in Figure 2).

| Northern Ireland | Scotland | Wales |

| Regional Domestic and Non-Domestic Rates | Business Rates | Business Rates |

| Direct, long-haul Air Passenger Duty | Scottish Rate of Income Tax | Welsh Rate of Income Tax |

| Corporation Tax (unused) | Stamp Duty Land Tax | Stamp Duty Land Tax |

| Landfill Tax | Landfill Tax | |

| Air Passenger Duty | ||

| Aggregates Levy | ||

| NOTE: plus assignment of VAT revenue. (unused) |

Figure 2: Devolved fiscal powers (sources: Scottish and Welsh Fiscal Frameworks)

As can be seen from Figure 2, NI has fewer fiscal powers than Scotland and Wales, and one of those (i.e. Corporation Tax) has never been exercised by the Executive.

But what does this mean for NI? To some extent, it means that the NI budget is shielded from the direct revenue impacts of COVID-19. For example, the Executive does not have to plan for reduced income tax receipts as a consequence of the economic shock caused by lockdown.

To illustrate when this can be an issue, an example is found in Scotland. The Scottish Government is already facing significant reconciliation payments because the income tax forecasts 2017/18, 2018/19 and 2019/20 were set on the basis of forecasts that – with hindsight – look to have been too optimistic. In simple terms, a forecast of revenue is made and the Scottish Government receives a Block Grant reduction equivalent to that amount to offset the devolved tax it raises. Then, there is a reconciliation between the forecast amount of tax revenue, and actual amount. If the adjustment based forecast is too low, the Scottish Government has to pay money back to the UK Government, and vice versa.

Having said this, there are some impacts at the NI level and these are considered below.

Air passenger duty

The Air Passenger Duty (Setting of Rate) Act (Northern Ireland) 2012 set APD rate to £0 for direct long haul flights departing from Northern Ireland. In line with the principles set out in the PFF, the NI Block Grant is adjusted to offset cost to the UK Exchequer (i.e. because NI set the rate to zero, the UK Exchequer collects no revenue from specific long-haul flights departing from NI).

According to the Executive’s Budget document, the cost to NI for 2020-21 is estimated to be £2.3 million. But, this estimate is based on the usual amount of air traffic. Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, almost all flights have ceased, and the skies have been almost free of vapour trails.

In an average year, in normal circumstances, £2.3 million would be lost to the UK Exchequer because of the Executive’s policy for long-haul flights departing from NI. But because of the significant reduction in travel for the last 3 months, all other things being equal, the consequential reduction to NI’s Block Grant is likely to be less than forecast. In turn, this should mean a small amount of additional funding would be available to the Executive to spend on other priorities.

The issue of rates, however, is more significant in scale.

Rates

RaISe paper 17/20 Assembly Committees – Coordinated Budget Scrutiny provides some detail on Executive policies and their costs:

The Executive agreed that Regional Rate will be frozen for domestic customers; and that Non-domestic business will see a 4p in the pound reduction – at a cost of £56 million. These costs have been met from within existing DEL budgets in the proposed outcome. The rates changes within the Budget proposed two COVID-19 related measures: Three month Rates holiday for businesses and delay bills until June.

The cost of the three-month holiday (£100m approx.) will be met from the first £120 million of Barnett funding received in respect COVID-19 response. There is no cost for delaying bills.

All in all then, the direct fiscal impacts on NI are likely to be relatively insignificant. But what about at the UK level? The fiscal impact is, of course, inextricably linked to broader economic impacts.

UK economic impact

As noted above, the limited fiscal devolution to NI means that the knock-on impact of the economic shock of COVID-19 will mostly be indirect: it will be shaped by the wider economic conditions across the UK, and the consequential reductions in tax revenues. Importantly thereafter, it will be mainly through the UK Government’s policy and future expenditure-planning responses that the NI budget is affected. As we have seen, the NI PFF dictates, these responses will then be transmitted to NI via the Barnett Formula – as shown above.

It is possible that in a future Spending Review, the UK Government may decide upon a big spending stimulus package. If it does, it is likely that the Barnett-determined fiscal transfers to NI would be relatively large. Conversely, if the UK Government attempts a drastic fiscal retrenchment to tackle quickly its ballooning deficit, the transfers to NI would be consequentially much smaller. Either way, the size of NI’s future spending envelope is largely out of the hands to the Executive that decides upon how best to spend it.

For these reasons, NI has to be viewed in the wider context of what is happening at the UK level. More data in relation to the economic impact of COVID-19 will become available over time, making more apparent the length and depth of the recession, and the strength of recovery from lockdown. Some factors are already clear, however:

1) Contraction in household spending – the Office for National Statistics (ONS) graphic below shows that, on average, just over one fifth (22%) of UK household spending in March 2019 was on items that were prevented by lockdown restrictions in Spring 2020.

Figure 3: UK household spending

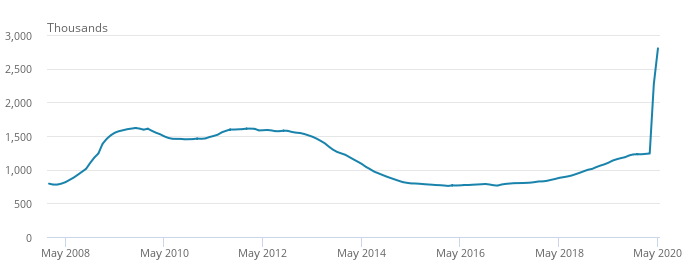

2) Surge in UK claimant count measure for unemployment benefit claims – the number of claimants has more than doubled in two months.

We can note from Figures 3 and 4 some important factors:

- Household spending is an important source of UK consumption-tax revenues such as Value Added Tax (VAT) – accounting for about one fifth of all UK tax revenue. It follows therefore, that if consumption falls, so would revenue; and,

- Income tax is an even more important source of revenue in the UK – accounting for about one third of all UK tax revenue. If more people are claiming out-of-work benefits, the income tax receipts would also fall.

On the other side of the tax-and-spend coin, certain expenditures would rise. As Mr Micawber famously observed in David Copperfield:

Annual income twenty pounds, annual expenditure nineteen [pounds] nineteen [shillings] and six [pence], result happiness. Annual income twenty pounds, annual expenditure twenty pounds ought and six, result misery.

At a public expenditure level, this ‘misery’ manifests in rising deficits, and over time as the deficits accumulate, rising national debt.

The Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) notes that COVID-19 has:

…led to an unprecedented increase in public deficits in peacetime. The Office for Budget Responsibility forecasts a budget deficit of £300 billion this year, more than 15% of UK GDP. Public debt is expected to exceed 100% of GDP by the end of the year.

The UK Government could respond to these facts in different ways, for example, by slashing spending, or seeking out new sources of tax revenues. The CEPR’s June 2020 survey of its Centre for Macroeconomics (CfM) panel asked about the urgency of deficit reduction and how this deficit reduction should be achieved:

Thirty panellists responded to this question. The panel was nearly unanimous (one dissent) that no measures should be taken in the upcoming budget.

Although the CfM panel did not totally agree on when or how the deficit and debt should be dealt with, they did agree that a response should not occur until after the pandemic has subsided.

NI Economic Impact

So far, this blog article has been concerned with the fiscal impact of COVID-19 at the UK level and how it may transfer to NI. But it is also crucially important to think about the likely impacts on NI expenditures, which must be met from the Block Grant.

Importantly, it should be noted that benefit payments are not met from the Block Grant under the current PFF in NI. The NI Executive forecasts the number of expected claimants, but the funding for benefit payments is transferred directly from the Treasury.

But there will be policy responses that – if prioritised by the Executive – would be paid from the NI Block Grant. The Department for the Economy’s (DfE) Rebuilding a stronger economy – the medium term recovery notes that:

Budgets are likely to be constrained over the coming years.

Constrained budgets inevitably mean competition between expenditure priorities, with the Executive balancing choices.

The DfE publication includes a number of proposed areas of ‘key growth sectors’, all of which will require some level of financial support, e.g.:

- Life and health sciences;

- Advanced manufacturing including automation/robotics;

- Digital; and,

- Clean energy.

It remains to be seen what response emerges to COVID-19 economic and fiscal effects. And of course, COVID-19 is only part of the picture. The clock continues to tick on the Brexit transition period and there are many issues still to be resolved in that regard. The DfE paper states:

All of these economic issues could be further compounded by the operation of the NI Protocol and EU Exit more generally. The lack of clarity on the Protocol and future UK-EU trading relationship limits our ability to fully indicate the level of these compounding economic impacts.

For more information on the range of EU-withdrawal issues, see RaISe’s six-part series of papers (paper numbers 25/20 to 30/20 on the Ireland/NI Protocol). And for a wider round-up of Brexit and transition related research papers from RaISe, see our Brexit Transition Hub.

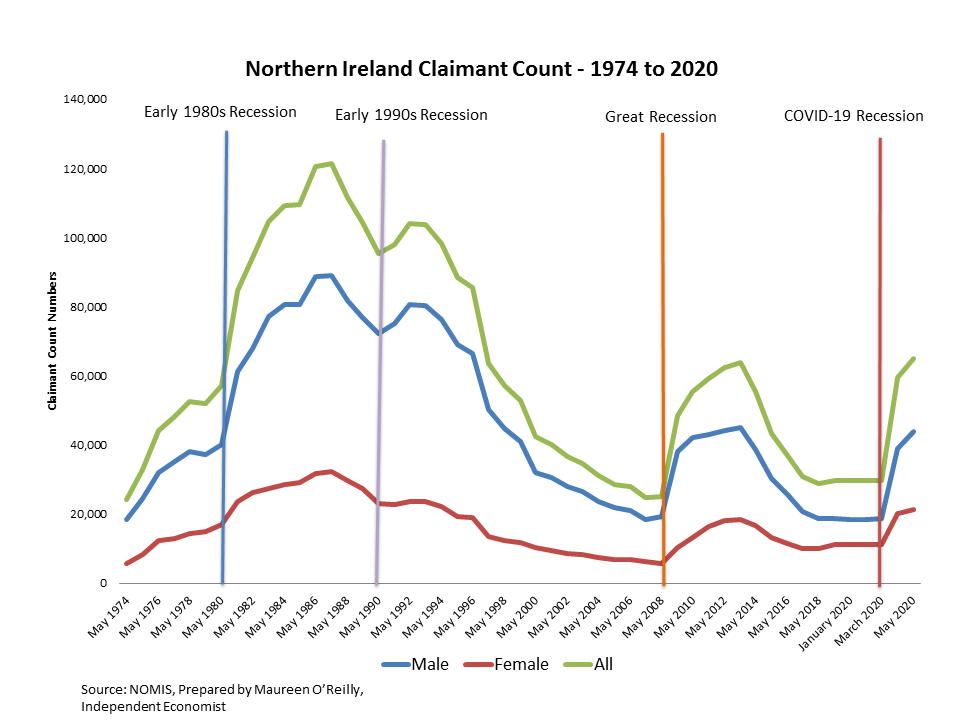

Whatever happens over the coming months, it will undoubtedly be difficult for many. But for context, it is also worth noting that although the current position on the NI claimant count is worrying, it was actually significantly worse in the late 1980s and early 1990s – see Figure 5 below:

As much as it may have been worse in previous decades, it remains clear that significant challenges lie ahead. The UK Government has tough fiscal choices to make, and those choices will largely chart the course of NI public expenditure in the coming years. The more restricted the future NI spending envelope, the more difficult the Executive will find it to finance investment in skills, apprenticeships or other labour market interventions. While some experts are warning that we should not be too optimistic, others see an opportunity to “build back better”.