Lough Foyle is a valuable ecosystem and fishery situated on the border between the UK and Republic of Ireland. The maritime boundary – and ownership of the Lough – has been disputed by the UK and Irish governments for a century. Nevertheless, the two governments have jointly managed the Foyle fisheries since the 1950s. However, new and emerging pressures are threatening the Lough’s ecosystem and economy.

This article accompanies a recent research paper by the Assembly Research and Information Service. It describes the Lough’s environmental and economic value, and the risks posed by unregulated aquaculture, climate change and pollution. It examines areas where cross-border governance has been successful, and where governance gaps are undermining sustainable marine management.

Background

Location

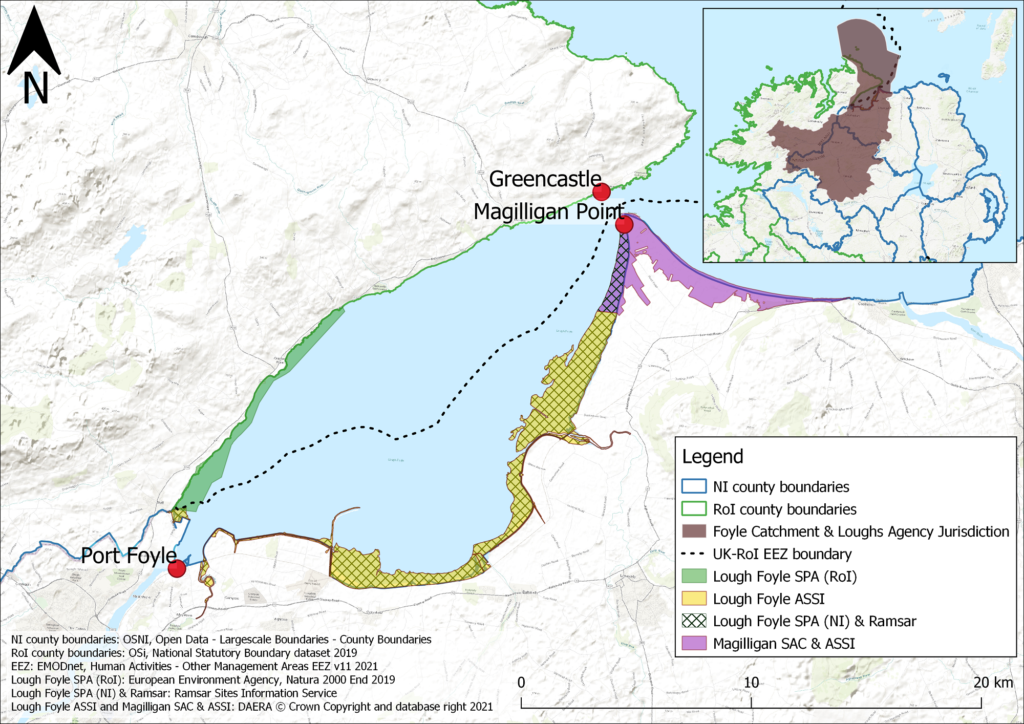

Lough Foyle is a large shallow sea lough located between County Derry/Londonderry in Northern Ireland (NI) and County Donegal in the Republic of Ireland (RoI).

History and governance

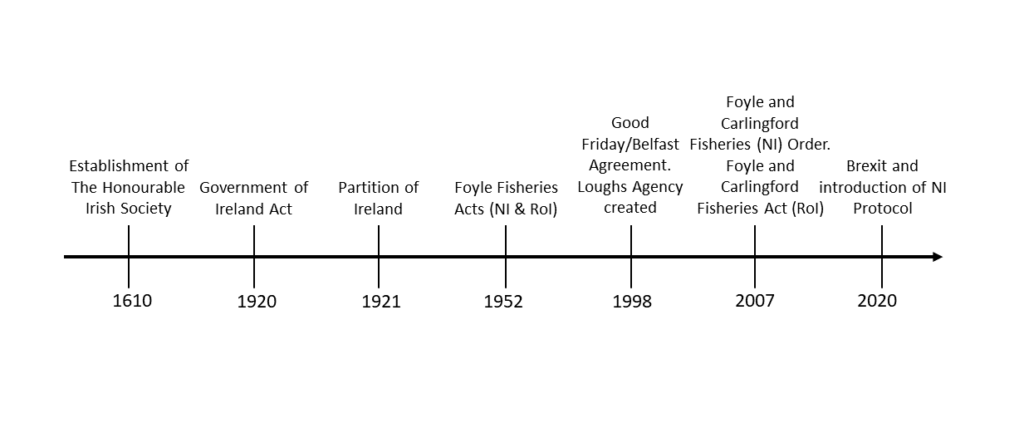

Lough Foyle’s valuable salmon and eel fishing rights were granted to the Honourable Irish Society in 1613, as part of the Plantation of Ulster. The partition of Ireland in 1921 left it unclear whether Lough Foyle belonged to the UK or the new Irish Free State. During the Second World War, poaching impacted the Foyle’s salmon stocks. In response, Stormont and Dublin introduced the complementary Foyle Fisheries Acts in 1952 (NI, RoI). The Acts created the cross-border Foyle Fisheries Commission to manage, conserve, protect and improve the fisheries in the Foyle area.

Following the Belfast (Good Friday) Agreement in 1998, the Commission was superseded by the new Loughs Agency. The Agency is part of the Foyle, Carlingford and Irish Lights Commission, which reports to the all-island North South Ministerial Council and its respective government sponsor departments in NI and RoI. The Agency is responsible for:

- Promoting commercial and recreational development of marine, fishery and aquaculture matters

- Managing, conserving, protecting, improving and developing the inland fisheries

- Developing and licensing aquaculture

- Developing marine tourism

The role and work of the Loughs Agency is summarised in the following video:

Recognising a need to regulate shellfishing in the Lough, the UK and RoI governments introduced The Foyle and Carlingford Fisheries (Northern Ireland) Order 2007 and corresponding Foyle and Carlingford Fisheries Act 2007. These gave the Agency additional legal functions and made it the ‘aquaculture licensing authority’. However, the ongoing jurisdictional ambiguity has prevented the full implementation of the 2007 Order/Act. As a result, the Agency cannot yet issue aquaculture licences. Since the foreshore and seabed are reserved and excepted matters in NI, full implementation will require the UK and RoI governments to agree who owns the Lough. This would allow the Agency to sign a management agreement with the owner/s of the Lough and start issuing aquaculture licences.

The UK withdrawal from the European Union on 31 January 2020 could potentially have an effect on cross-border governance. As EU member states, the UK and RoI had equivalent regulatory regimes in areas such as agriculture, environment and fisheries. These may diverge in coming years. However, Annex 2 of the NI Protocol currently limits the potential for regulatory divergence on some fisheries and aquaculture matters.

Aiming for sustainable management

The Loughs Agency aims to manage Lough Foyle sustainably on behalf of the UK and RoI governments. Sustainable management would:

- Protect the environment (the Lough has several Marine Protected Areas and an important native oyster bed);

- Facilitate ‘sustainable intensification’ of aquaculture to produce sustainable, low-carbon seafood; and

- Support rural jobs in aquaculture, fishing and tourism.

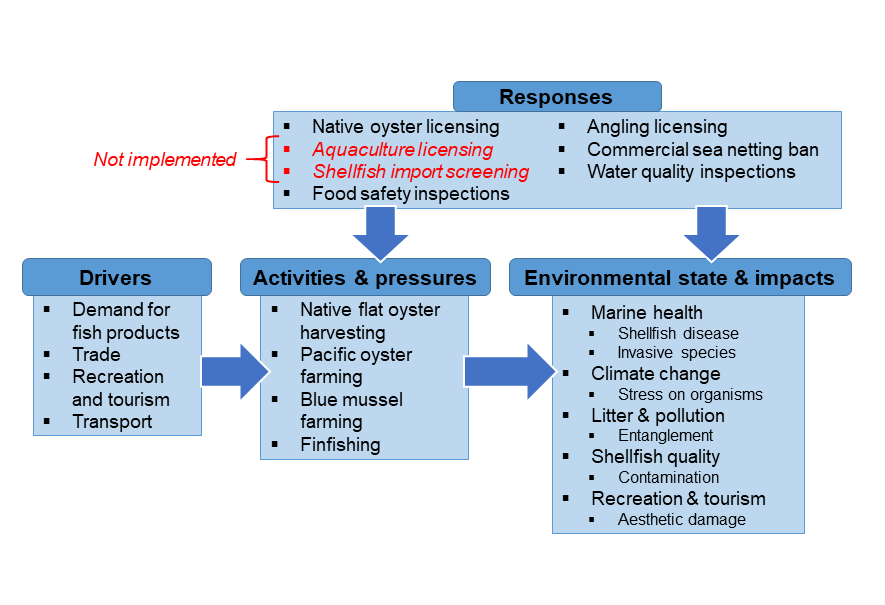

Lough Foyle’s marine system can be understood by considering how economic drivers and activities create pressures which affect the state of the environment, causing social impacts. The Agency is the main body that responds to these issues.

Opportunities: Activities and pressures

Lough Foyle offers opportunities for shellfishing, finfishing and marine tourism, although these can also create pressures.

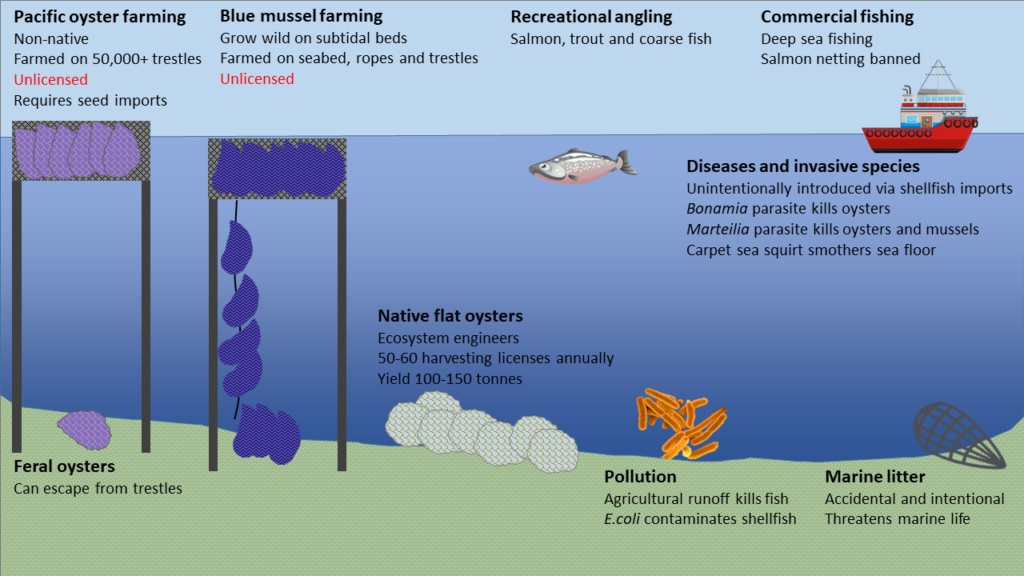

Native flat oyster harvesting

Native flat oysters occur naturally on Lough Foyle’s shallow sea bed. Once common in the British Isles, many oyster beds have sharply declined due to overexploitation. Oysters are a keystone species, forming reefs that provide a habitat for other species. However, native oysters reproduce sporadically and grow slowly. The Agency regulates native oyster harvesting to protect them from overharvesting. It currently licenses 50 to 60 native oyster fishers, yielding 100 to 150 tonnes, valued at around £400,000 each year. The main export market is Spain.

Pacific oyster farming

Pacific oysters were introduced to Ireland in 1965 for aquaculture since they can be grown easily and productively. In Lough Foyle, ‘seed’ Pacific oysters are imported to grow on trestles on the foreshore. Due to the jurisdictional ambiguity, the Agency cannot currently regulate oyster farming. As a result, unregulated farming has expanded rapidly, from around 2,500 trestles in 2011, to as many as 60,000 trestles in 2021. The Agency estimates that well-regulated, sustainable oyster farming could generate around £20 million each year in Lough Foyle.

Blue mussel farming

Blue mussels occur naturally in subtidal beds around the British Isles. Seed mussels are imported to the Lough to be farmed on the seabed, trestles or ropes. Mussel farming is currently a minor activity in Lough Foyle, but could expand and become valuable once again, although it is not yet regulated by the Agency.

Commercial finfishing and recreational angling

Finfish are ‘true’ fish, as distinct from shellfish. Historically, Lough Foyle and nearby seas were important commercial salmon fisheries. However, commercial salmon net fishing has been banned to protect declining salmon stocks. Greencastle and Moville in the RoI remain important commercial fishing ports. Recreational game and coarse angling takes place on rivers, the shore and the sea. The Agency sells rod licences and limits the size and number of fish caught. The Agency also tackles illegal activities such as fish netting, which may be reported by the public.

Recreation and tourism

Lough Foyle offers a range of recreational activities such as canoeing, boating, sailing, diving, shore fishing, coast walking and bird-watching. The Foyle Maritime Festival in Derry/Londonderry celebrates water-based activities along with food, music and arts events. In 2018 it attracted over 200,000 attendees and generated some £2 million for the local economy.

Risks: Environmental state and social impacts

Lough Foyle’s environment and economy are threatened by the potential introduction of disease, climate change, litter and pollution.

Marine health

Lough Foyle’s marine ecosystem is reasonably healthy. However, it is being threatened by new diseases and invasive non-native species. Bonamiosis disease is caused by a blood parasite of oysters. It has severely impacted many European oyster fisheries. It was detected in Foyle oysters in 2005, probably after being unintentionally imported. It is currently causing low levels of mortality.

Another disease – Marteiliosis – infects the digestive tissues of mussels and oysters. Fortunately, it has not been detected in Lough Foyle, and the Agency wants to reduce the risk of its introduction by strictly regulating seed oyster imports.

While not yet recorded in Lough Foyle, Carpet sea squirt is an invasive species that can smother the sea floor, vessels and equipment. Other potentially invasive species include slipper limpet, and Chinese mitten crab. Furthermore, farmed Pacific oysters can escape from trestle bags and, as the seas warm, these could potentially out-compete native oysters.

Climate change

Climate change is affecting the sea’s physical and chemical properties. Irish Sea temperatures are projected to warm by 2 to 3°C by 2100, while sea levels around NI could increase by 20 to 100 cm. Another consequence of increasing atmospheric CO2 levels is ocean acidification.

Sea warming, rising and acidification place stress on marine ecosystems. Diseases such as Amoebic Gill Disease may infect salmon more often, while invasive species originating in warmer seas could spread more easily. Furthermore, ocean acidification inhibits the growth of organisms with calcium-based shells such as plankton, oysters and mussels.

Litter and pollution

Lough Foyle is being littered by waste such as plastic trestle bags from unregulated aquaculture. This may entangle, or be ingested by, marine wildlife. Lough Foyle is also polluted by agricultural runoff, incidents of which have caused several river fish kill events. Faecal pollution and E.coli from untreated wastewater has a social impact, as Lough Foyle shellfish products are ‘class-B’ and must be purified to ensure they are safe to eat.

The key activities and pressures, and their impacts are summarised in the following diagram:

How can Lough Foyle be managed more sustainably?

The Loughs Agency is responsible for managing Lough Foyle’s fisheries sustainably. This task is complicated by cross-border issues, widespread unregulated aquaculture, emerging environmental threats and, potentially, by Brexit. The complementary UK and RoI 2007 Order/Act made the Agency the ‘aquaculture licensing authority’. However, the jurisdictional ambiguity and subsequent lack of a management agreement currently prevents it from regulating shellfish farming.

In response to a 2018 Northern Ireland Affairs Committee report, the UK Government stated:

The Government recognises the need to take action to address illegal shellfish farms that have been established on the side of Lough Foyle that borders Ireland. We are committed to working constructively towards a practical resolution to the issue. Discussions between the UK and Irish Governments are progressing on the jurisdictional issues with a view to concluding a management agreement to address this activity.

Whatever the outcome of discussions between London and Dublin, closer north-south cooperation will be required to safeguard Lough Foyle’s valuable ecosystem and the economy it supports.