What next for the environment, Brexit and cross-border co-operation?

Environmental regulation currently experienced by Northern Ireland (NI) and the Republic of Ireland (RoI) is greatly influenced by European Union (EU) policy frameworks. While some frameworks, such as the Water Framework Directive, and the Birds and Habitats Directives, are directly related to protecting the environment, there are other areas, such as trade, which require environmental standards to be met under trading standards. For example, the Customs Union controls quotas and tariffs for goods and enforces rules that provide for environmental protection and the safety of humans, health and animals.

This article explores some of the areas of concern that have been expressed in relation to potential impacts of Brexit on the environment, focusing in particular on regulatory divergence, enforcement issues, and the potential mechanisms and structures of cross-border co-operation.

Regulatory divergence

According to a House of Commons Library paper, environmental law is likely to be affected by Brexit through the following factors:

- The outcome of the Brexit negotiations;

- The approach of the UK Government and the devolved Administrations post-Brexit;

- The historical compliance record of the UK with EU requirements; and

- Whether it is an area that integrates with wider policy or legislative areas (e.g. product regulation and trade).

We don’t yet know what any final deal with the EU may look like, nor what structures may replace the role currently played by EU institutions, but a White Paper on the future UK and EU relationship (July 2018) implies that a ‘common rulebook’ could be applied to goods to ensure the UK meets product standards of the EU. According to the White Paper this would ‘remove the need to undertake additional regulatory checks at the border – avoiding the need for any physical infrastructure, such as Border Inspection Posts, at the border between Northern Ireland and Ireland’.

Concerns have been raised in relation to how this ‘common rulebook’ will impact future trade deals with non-EU states. That being said, the full impact of this may not be known until there is further clarity on how many EU goods standards are in fact globally/internationally driven and likely to still be in keeping with non-EU countries signed up to similar agreements.

The White Paper states that the UK Government has committed to continuing to uphold its international environmental obligations. This is in line with the European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018, which aims to copy over all environmental EU law into domestic law from the day of exit.

However, it is not yet known whether either side of the Irish border could eventually be working to different environmental standards and requirements due to regulatory divergence over time. Moreover, it is not clear how much say NI will have over setting its own agenda in certain environmental areas. For example, the House of Commons Library paper, ‘Brexit and the Environment’, considers the application of the Birds and Bathing Water Directives as discussed by the Welsh Government in Brexit and Devolution: Securing Wales’ Future (June 2017). The Welsh Government has stated that:

Some existing EU frameworks, for example, those created by the Birds Directive or the Bathing Waters Directive, are not primarily motivated by internal market considerations, and there may be no need to retain a UK-wide regime for these. This does not mean that the protections achieved by such Directives should be withdrawn; the point is rather that it should be for the responsible governments in each part of the UK to have the freedom to decide.

International agreements

There is also the issue of whether, post Brexit, the UK will continue in its own right to be a signatory to international environmental agreements that have been signed up to by the EU on behalf of its Member States. This is discussed in more detail by a previous blog post: How much change can we expect to current environmental requirements post Brexit? and the UK Environmental Law Association on the UK and international environmental law after Brexit.

What now for the Habitats Directive?

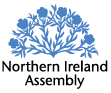

Currently, in both NI and RoI, the Habitats Directive is one of the main drivers for biodiversity conservation. Article 6 gives protection against development to designated sites and species. There are a number of designated sites under the European network of Special Areas of Conservation (SACs) and Special Protection Areas (SPAs) that span the border area, such as Lough Foyle, Pettigoe Plateau and Cuilcagh Mountain. Examples of SACs can be seen in Figure 1.

The Environmental Pillar (a consortium of 26 environmental NGOs in Ireland) has expressed a need for a common approach north and south of the border for nature conservation. According to the Environmental Pillar, one in five species on the island of Ireland are endangered. Their main concern is any difference in approaches used north of the border, particularly if this results in different standards which could ultimately affect conservation practices and planning approaches.

According to a House of Commons Library paper, the UK Government has stated there will be no relaxation in environmental standards and that international environmental agreements will be upheld and rolled over. Indeed, the paper states that, for its part, ‘the EU is keen to maintain similar environmental standards on both sides of the border to prevent environmental ‘dumping”.

The recent UK 25 Year Environment Plan aims to introduce new environmental safeguards to improve the environment through delivering a ‘green Brexit’. That being said, the Environmental Pillar has expressed concern about the long term potential for the unravelling and weakening of certain legislative requirements. For example, could we see a divergence emerging over time in areas where the UK has maybe struggled with compliance in the past and been subject to infringement proceedings by the EU?

The UK Government’s commitment

In relation to addressing potential regulatory divergence, the Draft Withdrawal Agreement (in the ‘Protocol on Ireland/Northern Ireland’, page 108) has stated a desire to maintain ‘full alignment with those rules of the Union’s internal market and the customs union which, now or in the future, support North-South cooperation, the all-island economy and the protection of the 1998 Agreement’.

However, it is not yet completely clear what direction will be taken with new environmental legislation and policy in the UK and NI, and whether there will be much difference with the RoI in the longer term. Michel Barnier stated in a speech to the European Parliament in April 2018 that any agreement on the future relationship with the UK should include a ‘non-regression clause’ for environmental standards. In fact, the White Paper on the UK and EU relationship (12 July 2018) stated the UK’s intention to agree a non-regression principle to maintain current environmental standards. This is despite concerns raised by Michael Gove in April 2018 to the House of Commons Environmental Audit Committee.

With this in mind, on 12 September 2018, Michael Gove introduced the Agriculture Bill, which aims to deliver a ‘green Brexit’ through a new Environmental Land Management system. It aims to replace the current subsidy system of Direct Payments with a new one which will pay farmers and land managers for ‘public goods’. This means farmers and land managers who provide the greatest environmental benefits will secure the largest rewards. This difference in approach to farming and land management either side of the border may present problems in the future both administratively and physically, particularly if one side is seen as more rigorous than the other. The Bill completed committee stage in the House of Commons in November 2018. The date for the next report stage and third reading is yet to be released.

Key questions still remain around how much input NI will have in developing any new UK wide framework: what freedom will NI have in shaping their own frameworks and how much might these differ from the RoI?

Enforcement

A consultation on a new (England only) body to hold the Government to account states that:

Once we leave the EU, and regardless of the nature of the future relationship we negotiate, we will no longer be a party to the EU Treaties or under the direct jurisdiction of the CJEU…without further action, accountability for the environment will change once we leave the EU, regardless of the future relationship we negotiate with it.

In response to this consultation, a draft Environment (Principles and Governance) Bill was published on 19 December 2018.

The Environmental Pillar has expressed concerns at the NI level that:

…without formal oversight by the European Commission and the European Court of Justice, a significant ‘governance gap’ could open up in the system of environmental law enforcement in Northern Ireland, leading to a de facto weakening of environmental protection on the island of Ireland.

On this basis the House of Lords Select Committee report recommended the need for an independent domestic enforcement mechanism.

Before the NI Assembly elections in March 2017, discussions were still ongoing about the introduction of an Independent Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in NI. Therefore, it is still unclear whether enforcement would be carried out by a similar NI body, or a UK-wide body. Again this raises questions in relation to whether the two sides of the border will be answering to different enforcement bodies with different standards, processes and requirements.

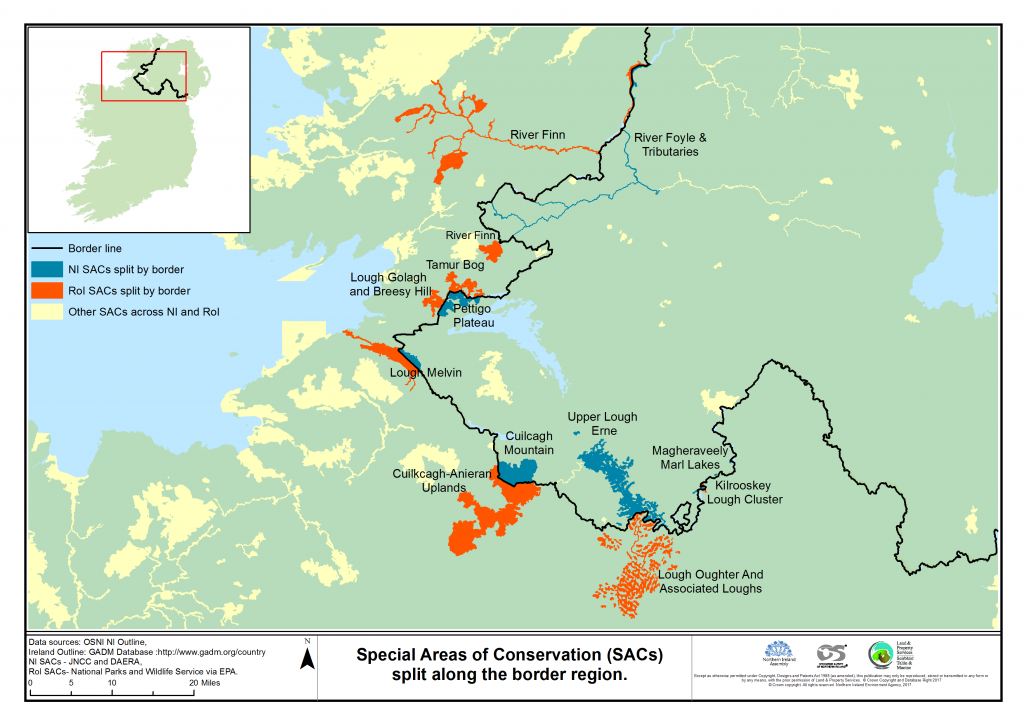

That being said, non-EU Member States can be in a collaborative relationship with the European Environment Agency (EEA), as can be seen in Figure 2. Further consideration may be needed to explore whether retaining membership of the EEA would help to facilitate cooperation and harmonisation of approaches between the UK and the RoI.

Continued co-operation

Under the Northern Ireland Act 1998 and the Good Friday Agreement 1998, the North South Ministerial Council (NSMC) and the British-Irish Council (BIC) were formed to provide forums for co-operative relationships and development of common policies either side of the border in a number of areas. Environment was identified under the Good Friday Agreement (Strand 1 Annex) as one of the key areas for ‘North- South cooperation and implementation’ by the bodies. As Brexit unfolds, these forums may be of particular importance to ensure that development regulation and environmental standards either side of the border strike the right balance between environmental protection and development opportunities. In fact, a recent report on the Good Friday Agreement, Brexit and the Environment explores this in more detail.

In a statement in October 2017, the then Secretary of State for Exiting the European Union, David Davis, stated that,

Our teams have also mapped out areas of cooperation that function on a North-South basis. And we have begun the detailed work to ensure this continues once the UK has left the EU.

The Draft Withdrawal Agreement (March 2018) provides for a Protocol for Northern Ireland/Ireland. Details of the Protocol have yet to be released but the draft agreement stated that ‘the negotiators agree to engage urgently in the process of examination of all relevant matters announced on 14 March and now under way.’

The House of Commons NI Affairs Committee published its report ‘The land border between Northern Ireland and Ireland’ (March 2018). The Committee recommended that the Government put forward targeted proposals for how cross-border cooperation in policy areas dominated by EU law will continue after the UK leaves. In relation to the political situation in NI, the report states,

…in the event of the restoration of the Northern Ireland Executive, EU competencies could be devolved to Northern Ireland so it can balance maintaining UK wide frameworks with EU alignment for cross-border policy areas. In their continued absence, alternative means of taking decisions will have to be devised.

The committee also commented on uncertainty regarding funding for cross-border projects:

The Government should clarify in its response to this report whether it will seek to continue funding for cross-border projects under the Interreg programme post 2020. If it is the Government’s intention to replicate this funding through the UK Shared Prosperity Fund it should specify the amount of funding it will make available, whether this money could support cross-border projects in Northern Ireland and the border regions of Ireland and what its spending priorities will be.